Sales arrangements and adding value to Botswana Diamonds

A divergence of interests between Botswana and De Beers

– Sheila Khama

Nov 2023

Introduction

This is the third of four articles on Botswana’s diamond industry. The first focused on the legal and institutional frameworks, while the second focused on the operations of joint ventures (JVs) between the Government and De Beers. In this article, I comment on the country’s quest for value addition by leveraging Sales Agreements between Botswana and De Beers to create a cutting and polishing industry. I critically review the effectiveness (or lack thereof) of the approach and other policy initiatives aimed at leveraging Debswana diamond production. As with the first two articles, I rely on governance and sustainable development principles to comment on what I believe works or does not work.

Background

Botswana is a leader in the mining, sorting, and valuing of gem diamonds, thanks to De Beers’ discoveries and the partnership between the company and Botswana in Debswana and Diamond Trading Company Botswana (DTCB) JVs. Through Debswana, Botswana and De Beers produced about 24 million carats in 2022 and rank second by volume after the Russian producer Alrosa and first by value. Not surprisingly therefore, the relationship between Botswana and De Beers attracts a lot of attention in and outside the country. In the past 12 months, media interest has been fuelled by negotiations for the renewal of the agreement between Botswana and De Beers for the sale of a portion of Debswana production. A quick internet search generates many articles on the matter, including in The Economist, The Financial Times, Reuters, Intelligence News, Rapaport and JCK Magazine. In this article, I add a citizen’s voice. I focus on Botswana’s quest for value addition through cutting and polishing and what this might mean for the marketing arrangements between Botswana and De Beers in the short term as well as what it might mean for the company’s marketing strategy and the relationship with the country in the long run.

Significance of Sales Agreement

While the right to develop a future mine is a company’s most important investment consideration at exploration, at the mining stage, the ability to sell the product, recoup investment and repatriate profits is supreme. It is an essential consideration for equity holders and investors considering investment in mining projects. Equally, for banks to provide project finance, for example, mining companies must give the assurance that they have secured these rights. Therefore, a central feature of the suite of agreements that mining companies enter into with host governments relates to terms of a Sales Agreement (also known as an off-take agreement). Referring to sales arrangements between his country and De Beers in a speech delivered to an audience at the African Development Bank in Tunis in 2009, former President Festus G.Mogae said the following in relation to the 1969 agreements: ‘It was also agreed that the marketing agreement would be renegotiated every five years. In return the Government accepted the single channel marketing that is to sell only through the De Beers Central Selling Organisation now known as the Diamond Trading Company’. – (https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/botswanas-former-president-discusses-african-extractive-industries-2358). The agreement has been implemented and honoured by both sides and renewed every five years until 2011, when the duration of the agreement was increased to 10 years. Hence the negotiations that were concluded in June 2023. That is to say, the negotiations that started in 2021, were not a function of a revised government policy but rather a continuation of a 50 year old framework for the Debswana and subsequently DTC Botswana jvs.

De Beers Rough Diamond Marketing Strategy

It is worth pointing out the significance of the statement by the Former President. The Former President’s choice of phrase ‘single channel’ is the language De Beers used at the time to articulate the company’s own marketing model. The phrase imports several important strategic implications whose meaning and impacts Botswana presumably understood. In its most simplistic form, the statement means that De Beers was granted exclusive rights to sell Debswana’s production, based on its sorting, valuing, and pricing systems. The valuation was and remains subject to the Government’s right to review using an independent Government Diamond Valuator (GDV). Though exclusive rights to sell mineral production are common in the mining industry, a number of factors differentiate the De Beers system. The first is that because diamonds are not traded in global commodity markets, De Beers (and other producers) has devised its own systems for valuing and pricing diamonds. Among other things, De Beers has developed a system of three-year contracts and criteria for selecting and selling to clients. – (https://www.debeersgroup.com/about-us/our-operations/sales/global-sightholder-sales).

A second feature of the system is that rather than sell production from different countries in which it mines or has partnerships separately, De Beers aggregates all its production worldwide to create parcels for sale to clients. Again, this practice is common for companies procuring minerals from different mines or buying from different suppliers. It is particularly so in case of homogeneous commodities such as gold or oil, for which here is a global benchmark like Brent Crude. But diamonds are different because the gems cannot be chemically fused together. Equally no two diamonds are the same and so the aggregation of diamonds calls for judgment and becomes discretionary. In case of De Beers for instance, large diamonds are valued individually, while smaller, lower-quality parcels are valued using a representative cut-off. That value is ascribed to the balance of the diamonds from a run of mine and with the same description. De Beers’ motivation for aggregating is to provide consistency of product to their customers over time, meaning sustainability and some predictability of price. In this regard, it is worth noting that De Beers voluntarily subjected its pricing systems to EU regulatory scrutiny to ensure full compliance with anti-trust laws and the system was deemed market friendly and compliant with principles of fair trade. – (https://mg.co.za/article/2002-01-01-de-beers-gets-eu-backing-for-diamond-sale-overhaul/?amp).

In addition, to support its valuing operations, De Beers designs its own systems and technology for sorting, valuing, pricing, and selling. The know-how is proprietary to the company and deployed exclusively in its own operations and those of JVs. As such it is not sold in the open market. In the diamond industry, the technologies, intellectual property, and the company’s investment in advertising is considered by many to be one of the company’s strongest value propositions to its partners. Specifically, commentators attribute the growth in the price of rough diamonds and demand for diamond jewellery relative to other precious stones to a combination of these factors. – (http://www.cssr.uct.ac.za/sites/default/files/image_tool/images/256/files/pubs/MMCP%20Paper%206_0.pdf).

Coming back to arrangements with Botswana, acceptance of a single-channel marketing system, therefore, was Botswana’s endorsement of this comprehensive business model and is integral to De Beers’ long-term commitment to invest in Botswana. These arrangements lie at the heart of De Beers’ rationale for the initial capital investment in mine development and subsequent decisions to use its share of the free cash flow from Debswana to reinvest in technology and mine infrastructure. An important question is whether the company is justified in its expectation that this arrangement and other parameters for the partnership remain perpetually unchanged. In other words, can a country’s right to self-determination as relates to sustainable development of its mineral resources be defined by the strategy of a private company and partnership arrangements therein?

Botswana’s Approach to Diamonds Value Addition

Agreements notwithstanding, national development goals and economic needs change with time. As the changes occur, they impact agreements with partners, especially those that relate to long-term investments in extractive resources projects. As such, the Former President’s words mask a glaring reality. That is the country’s beneficiation strategy through cutting and polishing should balance changing development aspirations with provision of a stable investment climate for its partner De Beers. The challenge of achieving this balance is neither unique to Botswana nor to Africa. It is often made more difficult by the fact that it straddles national politics and mineral economic policy. Typically, whenever the subject of value addition enters public discourse, it is presented either as an entitlement to the Government as the owner of the resource, as populist rhetoric to gain electoral support, a clearly laid-out industrial development policy or for that matter a combination of all three.

In this respect Botswana is no exception. The subject of value addition through diamond cutting and polishing started as a political debate, although with economic undertones. The subject was first raised in the late 1970s and to facilitate the establishment of the sector, one of the first things the country did was enact the Diamond Cutting Act in 1979. The matter gathered pace in the 1990s, with advocates arguing that cutting and polishing Botswana’s diamond production would be a vehicle for extracting more economic value through job creation. At the time, De Beers resisted the idea. Among other things, the company argued that retaining a portion of Botswana’s production would undermine its system of aggregation, affect the price of rough diamonds adversely and potentially reduce revenue to Debswana JV partners. Furthermore, the company argued that relative to other cutting and polishing centres, Botswana was uncompetitive, and that the proposed change in marketing arrangements would introduce inefficiencies in the value chain, further impacting income from Debswana adversely.

To independently assess the country’s competitiveness, the Government of Botswana commissioned a study on the feasibility of a thriving cutting and polishing industry in 1996. The conclusion was that Botswana could not compete with other diamond cutting centres such as Mumbai and Bangkok. The main challenges were lack of cutting and polishing skills, a comparatively high unit cost of labour and low levels of productivity. Nevertheless, the Government did not address the findings of the study as such, and instead the matter of beneficiation continued largely as a political bone of contention that unified all political parties. Importantly, De Beers’ position, and not formulation of policies to address the findings of the report, became the point of reference, with critics arguing that De Beers was unsupportive of national interests. The first cutting and polishing factory was Diamond Manufacturing Botswana, established in the late 1980s by an independent. In 1997 however, due to pressure, two other factories supplied with aggregated goods from De Beers were opened in Molepolole and in Serowe respectively. But the Government and the public demanded more. Facing public and political pressure, the Government saw negotiations for the renewal of the Jwaneng mining license and Sales Agreement in 2004 as an opportunity to leverage its position and demand that De Beers alter its terms of marketing Debswana diamonds to accommodate the Government’s desire to establish a bigger diamond cutting and polishing industry.

Conflicting interests based on De Beers’ commitment to its model and Botswana’s desire to become a centre for cutting and polishing stemmed from the potential for the Government’s demands to undo the company’s strategy of channelling the sales of diamonds through a single avenue. This had been an important cornerstone of the company’s marketing strategy for more than 60 years since it was established by Sir Ernest Oppenheimer in 1948. Though modified to be demand-focused rather than supply-driven, the system remains central to the company’s rough diamond distribution operations. For its part, the Botswana Government’s strategy was to leverage its position as De Beers’ largest source of diamonds and revenue by pressing the company to align with its vision. In not so many words, the negotiators implied that if De Beers did not toe this line, the country might be forced to pursue less amenable ways to achieve its goals.

De Beers was well aware of the political and public sentiment, having conducted an opinion survey among Batswana stakeholders in preparation for the 2004 negotiations for renewal of the Jwaneng mining licence. Hence, having started on opposite sides, in the end the Debswana JV partners ended up being pragmatic. While the Government was motivated by a combination of development and political goals, the company’s motives were commercial, but each wanted to bring closure to negotiations. Importantly, the JV partners understood the risk of failure and accepted that collaborating to find a solution to the uncompetitive cutting and polishing business environment in the country was a better remedy. Both saw working together as an elegant way of breaking the deadlock and deflecting any perception by the Botswana public that the Government team had baulked or that De Beers had once again dug in its heels. So, a deal was reached and the DTCB JV was created to be an agent for De Beers and to market diamonds to Botswana’s cutting and polishing factories. Thus, in addition to De Beers distribution offices in London, the JV partners had created a second means to sell aggregated parcels while remaining within the single-channel marketing arrangements. De Beers was content in the knowledge that, as related to sorting and valuing processes, marketing systems, and pricing methods, the DTCB operations were aligned to the company’s marketing model. In negotiation terms therefore, it was a good outcome because each side had secured its original strategic position but it masked a growing clash of interests.

Attracting Investment in Botswana’s Cutting and Polishing Value Chain

While the above arrangement addressed the deadlocked negotiations, it did nothing to address the fundamental problem of Botswana’s lack of competitiveness. Therefore, to address the challenge, it was agreed that De Beers would identify 10 of its clients considered most likely to withstand Botswana’s otherwise unfavourable manufacturing conditions. The businesses were selected based on their financial muscle, company economies of scale, and on the ability to leverage experiences of their operations elsewhere. In addition, diamonds supplied to the factories were carefully selected based on what were considered economically cuttable stones, so as to insulate those businesses from market downturns. These goods were generally considered to be at the more profitable end, with historically higher margins needed to offset high costs. So, Botswana granted Precious Stones Dealers Licenses (PSDL) to these businesses based on the assessment and recommendation by De Beers.

It is worth remembering that all over the world, demand for rough diamonds far outstrips supply, and like their competitors, most De Beers clients are unable to secure adequate supply to meet business requirements. Therefore, as a condition for opening factories in Botswana, in addition to receiving supply by De Beers for their operations elsewhere in the world, the companies were also guaranteed supply in keeping with their business plans for their Botswana operations. This second source of supply attracted the companies to Botswana and compensated for the country’s uncompetitiveness. This advantage relative to their competitors not invited by De Beers and Botswana to set up factories in the country motivated the first 10 companies to establish operations in 2008. By the end of the five year sales agreement cycle, the annual value of the supply was US$550m, but the environment remained challenging. A 2013 study by the European Centre for Development Policy Management (ECDPM) (more than 10 years after Botswana’ study) concluded that Botswana remained uncompetitive. – (https://ecdpm.org/work/from-growth-to-transformation-what-role-for-the-extractive-sector-volume-2-issue-2-feb-march-2013/diamond-beneficiation-in-botswana).

As a result, even with a head start, investors struggled, and some factories closed, including one of the first three that was based in Serowe in the 1990s and after first changing ownership. Commentators remain convinced that Botswana cannot compete with Asia based on a unit cost of labour and productivity. This should not come as a surprise, nor is it a reflection on Botswana per se. It is a statement of the levels of skills, efficiencies, economies of scale and productivity in manufacturing industries across the board in Southeast Asia, China, India, and Indochina. The rest of the world, including the EU and US, struggle with the same challenge and have devised strategies for competing including focusing on unique areas of advantage. But in Botswana, the question of what policy interventions were necessary to address the competitiveness gap was neglected. – (https://mg.co.za/article/2015-02-19-botswana-diamond-workers-bleed/).

2011 Renegotiation of the Sales Agreement

The 2006 Sales Agreement between De Beers and Debswana was due for renewal in 2011. The Government took the opportunity to increase De Beers’ supply to cutting and polishing factories. The outcome was that by 2022, the annual value of supply nearly doubled and reached US$950m, with 39 De Beers sightholders. A second outcome from the negotiations was an increase of the duration of the Sales Agreement, from 5 to 10 years. In addition, the Government created a State Owned Enterprise (SOE), known as Okavango Diamond Company-ODC, to share production of Debswana’s goods with De Beers and market it separately. Originally, Debswana supplied the SOE with 12% of production and unlike De Beers the SOE auctioned a portion of Debswana (only) diamonds online. But the pre-viewing meant that potential buyers had to travel to Botswana to view the diamonds in advance. The significance of the SOE auctions was that for the first time since 1969, Botswana sold unaggregated Debswana diamonds. The split in production and sale of Debswana goods separately meant that two of the most important aspects for De Beers’ single channel system were impacted. That said, the SOE did not have any obligation to supply the factories established in 2008 and for 15 years from 2008 to 2023 only De Beers supplied the factories. A final outcome of the 2011 negotiations was the conclusion of arrangements for De Beers to relocate the company’s distribution arm from the UK to Botswana. This followed principle agreement in 2006, but the terms and conditions of the move were finalized in 2011, and the move finally happened in 2012. The relocation added a modest 230 jobs to Botswana’s employment numbers. However, the move also added significantly to Botswana’s international trade figures in terms of imports and additional exports of diamonds. This had the incidental but significant benefit of increasing Botswana’s entitlement to revenue distribution from the Southern Africa Customs Union (SACU) revenue pool.

2023 Renegotiation of the Sales Agreement

The next round of negotiations to renew the Debswana Sales Agreement with De Beers started 10 years later in 2022, but progress was hampered by the COVID-19 pandemic. So, the agreement was extended to the end of June 2023. In addition, and in anticipation of the investment in building the Jwaneng underground mine and associated infrastructure, the Government and De Beers agreed to concurrently negotiate the renewal of the Debswana mining licences. Commitment to make the investment is predicated upon several factors, the most important of which is security of tenure which is addressed through renewal of the licences. A second important factor is the ability to recoup the investment, which is determined in part by the terms of the Sales Agreement. Thus, though the licenses do not expire until 2029, the rationale for the concurrent negotiations is that the two agreements need to be finalised prior to the investment being made. This is especially so because in order to guarantee business continuity, associated costs will be incurred, and the investment made before 2029. Regarding the Sales Agreement, the Government’s main desire was once again to increase the supply of Debswana diamonds to the SOE, while De Beers’ goal was to retain as large a share as possible.

On June 30, 2023, the parties announced that the main terms of the Sales Agreement had been reached, and that it would be extended by a further 10 years until 2033. Further that Debswana’s supply to the SOE would increase immediately from 25% of the run of mine which is expressed in US dollar value of carats produced. That the share of production to the SOE would increase incrementally such that ODC’s share immediately increased to 30%, becoming 40% in five years, and 50% by the 10th year. In the new dispensation, the 50% equity in Debswana appears to have been used to argue for parity by sharing equally in the run of mine production. Seen this way, the latest sales arrangements are indeed transformational, because they have moved from a sales arrangement to a Production Sharing Agreement (PSA) between the shareholders of Debswana. But while De Beers’ supply of Botswana factories will increase from US$950m to US$1b, as part of the initial announcement, there was no reference to the SOE obligation to supply Botswana-based factories. Instead, the announcement referenced the SOE supplying citizens in possession of PSDLs.

According to De Beers, the split of financial distribution from Debswana was left at a ratio of 80.8:19.2 on the dollar in favour of the Botswana Government – https://www.jckonline.com/editorial-article/de-beers-botswana-made-deal/. Between future investments in mine development and reduction in share of production and therefore a fall in sales commission to De Beers, it is hard to see how the profit split can remain at this level without disincentivizing De Beers in the long run. Perhaps the short term solution lies in part in the fact that, having ceased contribution towards De Beers’ marketing budget in 2006, (as was the case for all companies selling through De Beers), following the latest agreement, that arrangement will apparently be reinstated such that the SOE contributes towards advertising costs. How the contribution will be decided and what the amounts are, has not been publicised. But it does reduce De Beers costs and increases those of the SOE. Debswana operational efficiencies, and the highly profitable nature of the Jwaneng deposit on the other hand, must give comfort to AAC plc as profits continue to grow even in the face of lower Debswana production figures relative to pre-financial crisis figures of 2009.

Impacts on De Beers’ market share are another issue. The company’s current market share is estimated at 34%. The question is how the company adjusts to the new environment in which this market share will be reduced. The company has limited options including scaling down to become a smaller but more profitable company as was envisioned in the 2006 Supplier of Choice strategy. This might mean cutting down on investment in advertising, R&D in mining and sorting and valuing. On the other hand, subject to an end to sanctions against Russia by EU and US, one wonders whether an opportunity is legally available for De Beers to close the gap with a sales agreement with Alrosa or whether EU anti-trust laws rule this out. But if this manifests, Botswana could become less strategic to De Beers. Importantly, given that the Sales Agreement with Debswana expires in 2033, the logical question is what will follow post 2033? Will Botswana turn the tables on De Beers and become the main agent for the sale of Debswana goods? Undoubtedly, investment analysts in the city of London and AAC plc shareholders will be pondering these questions and only time will tell how the issues are addressed.

For its part, unless one assumes there is no tipping point, the Botswana Government needs to also ponder these questions and have a clear understanding of risks versus rewards. Of importance is a scenario in which De Beers might not be in the picture at all stages of Botswana’s diamond industry value chain. As such it begs the question of what response Botswana can eventually expect from the company? Is there a tipping point beyond which the trade-offs erode value? Can De Beers switch to alternative ways of marketing diamonds or an alternative supplier? Is Botswana’s goal to go it alone and replace De Beers? These questions are essential for the Government to consider in order to successfully mitigate the risk of unintended consequences while optimising the value of the country’s wealth. A calculated risk based on an understanding of what the tipping point is from De Beers’ view and a Plan B is presumably part of the Government’s plan. Otherwise in the long run, the risk rewards analysis might prove hard to justify.

What Has Worked

Negotiation Outcomes

Looked at purely transactionally, interim negotiations of the Debswana Sales Agreement have successfully contributed to Botswana’s beneficiation goals, especially since 2006. The creation of a cutting and polishing industry, leading to the establishment of 46 factories that employed about 4320 skilled personnel by mid-2023, is proof of this. The employment figures make the industry second only to Debswana, which employs 5500 people. However, the cutting and polishing figures are extremely modest relative to other cutting and polishing centres such as India, which has been in the gem-cutting and polishing business for centuries and employs an estimated 800,000 to 1 million people. – (https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/in/diamond_final.pdf). The cutting and polishing companies operating in Botswana are privately owned, so financial records, including levels of investment and tax payments, are not public. However, given the traditionally low margins in the cutting and polishing industry, and high start-up and operating expenses, it is highly unlikely the firms have adequate surplus income to pay corporate tax. Given the likely lack of profitability, it is therefore reasonable to assume that foreign direct investment (FDI) and employment creation are the main economic deliverables that can reasonably be expected from Botswana diamond cutting and polishing activities in the foreseeable future.

Public Revenue Stability and Predictability

One of the most important aspects of De Beers’ system of three-year sales contracts with the company’s clients is that the company guarantees the shareholders of Debswana regular income every five weeks from sales to its own clients. During peak production in 2008, payments to the Government averaged US$250m. Any reduction of diamonds sold by Debswana to De Beers will impact this revenue stream but will presumably be offset by ODC sales. Botswana needs the revenue. The August 2018 edition of New African Magazine featured story on the newly appointed President of Botswana, His Excellency President Masisi, lamented Botswana’s budget deficit. – (The Big Interview: Mokgweetsi Masisi – President of Botswana, newafricanmagazine.com).

De Beers Advertising, Demand, and Price

De Beers’ ‘A Diamond is Forever’ advertising campaign is credited with the growth in the price for rough diamonds relative to other precious gems, namely sapphires, rubies, and emeralds. In 2002 the United States Geological Survey estimated that in US market the price of diamonds had grown by 26%, in comparison to emeralds at 11%, and compared to a 26% drop for sapphires. Equally, the market for diamonds had grown by 62% in comparison to other gems, which had only grown by as little as 25%. But sustaining the upward diamond price trajectory is not cheap, and by the mid-1990s the annual advertising budget ran into millions. De Beers will undoubtedly be incentivised to incur the cost given the SOE cost sharing arrangement and this is a good outcome. In the words of an industry analysts, Richard Chetwode, ‘De Beers has also built a state-of-the-art diamond tracking system (Tracr) ‘best-in-class’ diamond grading (IIGDR), is the only diamond company to spend millions on R&D to defend the ‘integrity’ of natural diamonds… the list seems to go on and on, but all of these benefit Botswana. I challenge anyone to find a better deal in any other country’. – bne IntelliNews – COMMENT: The diamond industry is in crisis and Botswana is going rogue!

Leveraging De Beers’ Capabilities

Some of Botswana’s major achievements to date have been possible because of demands imposed by the Government on De Beers, rather than because of national policies and strategies. Whether the Government is funding or managing projects, starting in 1969 with mine development, building, funding Orapa House, constructing and equipping the DTCB building and selecting sightholders to locate in Botswana, the Government has played its cards right. However, some arrangements, including the exclusive use of De Beers’ systems and technology to sort Debswana diamonds, have deepened reliance on the company. The provision in the latest sales agreement for De Beers to set up and manage a Diamond Development Fund & Skills Transfer and more, is a case in point. Thus, this leverage might also be a double-edged sword because while Botswana leverages its strength, the outcome has been an over-dependence on De Beers. The question is how the Government can balance the two.

Investor Relations

Botswana has exhibited an unusual forward looking view of its relationship with De Beers by bringing forward the renewal of the Debswana mining licences by 6 years ahead of their expiry date. Through this gesture, the Government shows commitment to the Debswana JV. Though the licenses constitute a separate legal arrangement to the Sales Agreement, they are the bedrock of everything else and the primary source of revenue and market share for De Beers and the SOE. As such the decision is welcome because it pragmatically recognises that Debswana is the foundation upon which the future rests.

What Can Be Improved

Value-Addition Policy

The Government does not have a detailed policy for diamond value addition. Though referenced in Botswana’s 2022 Minerals Policy, the document is high-level and cuts across different minerals from upstream and midstream aspects of the mineral value chain. Thus, it lacks depth and specificity. The development and implementation of diamond beneficiation goals are seemingly guided by a strategy that is not published. Diamonds beneficiation is also addressed in a high-level multi-sectoral Industrial Development Policy as part of the African Growth and Opportunity Act’s (AGOA) five priority areas. This approach is too disjointed to permit monitoring and be impactful. – (https://agoa.info/downloads/national-strategies.html). Instead, historically, major milestones in Botswana’s cutting and polishing industry have revolved around the negotiations for the renewal of the Debswana Sales Agreements. This means that rather than being embedded in a policy framework, diamond beneficiation is driven largely by the outcomes of negotiations from which the initiative also derives momentum. But the idea that Botswana can substitute a properly structured and documented beneficiation policy with periodic negotiations with De Beers does not meet the standard for a long-term value addition or industrial development policy principles. The scope of the negotiations and outcomes are too narrow to cover all matters necessary for maximising the value of the country’s diamond resources. A better alternative is a policy based on clearly understood trade-offs with clearly articulated risks and rewards, including prospects to move into jewellery manufacturing. The policy would guide negotiations with investors because though an important tool for policy implementation, negotiations are not the starting point. A clearly laid-out and transparent policy would also manage investor expectations. Even more importantly, the policy would enable Botswana to improve the business environment and compete with other cutting and polishing centres.

To formulate a policy, greater understanding is required of how to transform the raw materials into a finished product and what accounts for the higher value. In the industry, technology, branding, research, the right industrial and commercial environment are necessary to nurture demand for luxury commodities. These are some of the factors that explain the higher value in finished goods. In other words, contrary to common belief, it is not the mere availability or easy access to raw materials that justifies vertical integration. In fact, raw materials are hardly a necessary condition, let alone a sufficient one. (Japan produces steel products without producing iron ore). Thus, whether Botswana successfully cuts and polishes diamonds is a function of industrial development policy and not an outcome of a Sales Agreement. Successive administrations appear to interpret De Beer’s acceptance of Botswana’s demands as adequate to replace a beneficiation policy and misconstrue outcomes of commercial agreements for economic development policy.

Value-Addition Policy

The Government does not have a detailed policy for diamond value addition. Though referenced in Botswana’s 2022 Minerals Policy, the document is high-level and cuts across different minerals from upstream and midstream aspects of the mineral value chain. Thus, it lacks depth and specificity. The development and implementation of diamond beneficiation goals are seemingly guided by a strategy that is not published. Diamonds beneficiation is also addressed in a high-level multi-sectoral Industrial Development Policy as part of the African Growth and Opportunity Act’s (AGOA) five priority areas. This approach is too disjointed to permit monitoring and be impactful. – (https://agoa.info/downloads/national-strategies.html). Instead, historically, major milestones in Botswana’s cutting and polishing industry have revolved around the negotiations for the renewal of the Debswana Sales Agreements. This means that rather than being embedded in a policy framework, diamond beneficiation is driven largely by the outcomes of negotiations from which the initiative also derives momentum. But the idea that Botswana can substitute a properly structured and documented beneficiation policy with periodic negotiations with De Beers does not meet the standard for a long-term value addition or industrial development policy principles. The scope of the negotiations and outcomes are too narrow to cover all matters necessary for maximising the value of the country’s diamond resources. A better alternative is a policy based on clearly understood trade-offs with clearly articulated risks and rewards, including prospects to move into jewellery manufacturing. The policy would guide negotiations with investors because though an important tool for policy implementation, negotiations are not the starting point. A clearly laid-out and transparent policy would also manage investor expectations. Even more importantly, the policy would enable Botswana to improve the business environment and compete with other cutting and polishing centres.

To formulate a policy, greater understanding is required of how to transform the raw materials into a finished product and what accounts for the higher value. In the industry, technology, branding, research, the right industrial and commercial environment are necessary to nurture demand for luxury commodities. These are some of the factors that explain the higher value in finished goods. In other words, contrary to common belief, it is not the mere availability or easy access to raw materials that justifies vertical integration. In fact, raw materials are hardly a necessary condition, let alone a sufficient one. (Japan produces steel products without producing iron ore). Thus, whether Botswana successfully cuts and polishes diamonds is a function of industrial development policy and not an outcome of a Sales Agreement. Successive administrations appear to interpret De Beer’s acceptance of Botswana’s demands as adequate to replace a beneficiation policy and misconstrue outcomes of commercial agreements for economic development policy.

Industry Sustainability

An essential question relating to value addition is one of the long-term sustainability of Botswana’s cutting and polishing industry. Given that the companies located in Botswana on the back of additional diamond supply, the question of what happens when Botswana is no longer able to compete based on availability of additional rough diamonds is one that must be addressed at the outset. The biggest policy shortcoming is that given the country’s goal of growing the industry, and having understood business environment challenges for decades, little has been done to improve country competitiveness. This includes lowering utility costs and requiring the supply of diamonds by all producers and not confining supply of local factories to Debswana and De Beers only production.

Crucially, the Government has not addressed skills shortage but passes the burden to the investors who have had to train employees from scratch. As a result, some have resorted to cutting large stones using technology because small stones are cut manually and in large quantities. However, it is the large quantities of small stones which explains the high levels of employment in India. To borrow from the words of one of Botswana’s opposition leaders, Mr Ndaba Gaolatlhe, addressing the Alliance for Progressives Party youth in May 2023, ‘we are not willing to invest in technical, industry specific skills. We are not producing craftspeople in any serious way in the sector.’ – (https://bgi.org.bw/sites/default/files/Botswana%20Minerals%20Policy%202022.pdf).

Long-Term Supply

Given that Botswana’s comparative advantage is the supply of diamonds, more should be done to attract investment in making additional discoveries. This is a better strategy than one in which the Government invites more cutting and polishing companies to compete for declining Debswana production instead of inviting them to invest in exploration and potentially grow the future pipeline. This is likely to improve the long-term sustainability of the value-addition goals. But the precursor is the country’s reputation. Recent remarks by the country’s leaders led observers and some members of opposition parties to question the wisdom of publicly disparaging comments about De Beers and its impacts on investor sentiment. Ratings from Transparency International and the Afrobarometer Survey validate the risk by pointing to a downward trend in governance. Hopefully, these are outliers since others still view Botswana positively. – (https://www.weekendpost.co.bw/37185/news/botswanashuman-rights-record-un-recommendations/).

Complex Distribution Structure

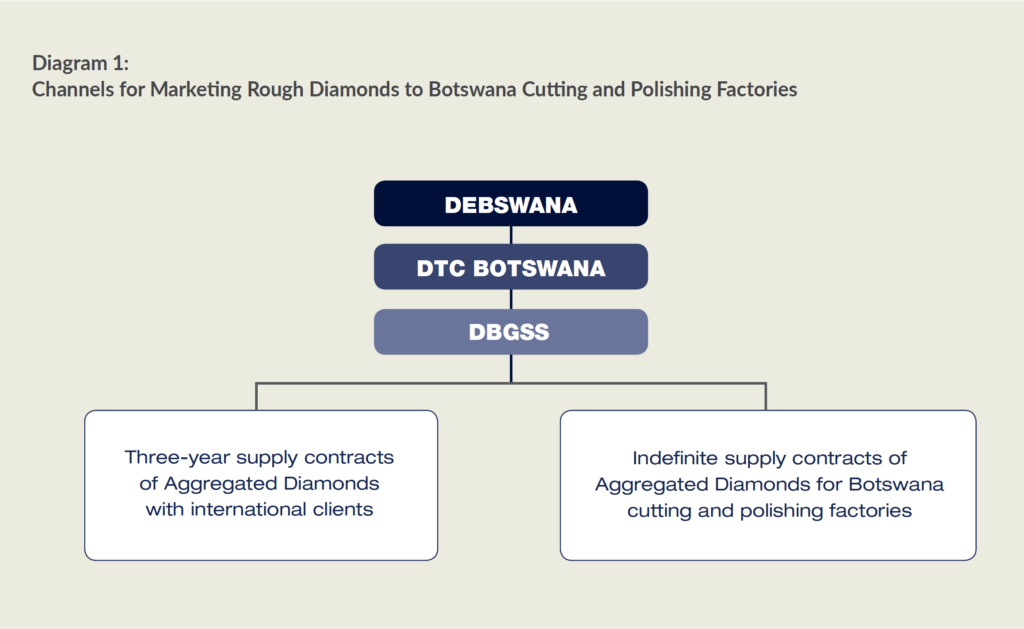

Through its investments, the Botswana Government has multiple channels for selling Debswana production but it is not clear how value enhancement is assessed and validated. Diagram 1 shows that between 2006 and 2012, the Government had equity in two companies in the country, through which it marketed a portion of Debswana diamonds using at least one separate system. The entities were DTCB and De Beers. The distribution channels were first confined to aggregated parcels sold by De Beers using mainly contracts. The creation of the SOE added another.

Conclusion

Starting with the 1969 Sales Agreement, the arrangements with De Beers have delivered incrementally to the State. Whether it was increase in the split of distributable income from 75% to the current 80.8% to the State, the increase of Botswana shares in De Beers Group from 7.5% to 15% without contribution and the funding of the world’s largest most modern diamond sorting house, Botswana has done well. The milestones and figures are impressive and make for a good victory lap. But one must ask what of long term impacts? One way of answering this question is by tracking the impacts of these deals on the economy and as such the people of Botswana. In the absence of the Government of Botswana having articulated an end state-vision which served as a policy point of departure for each negotiation strategy, this means development of country’s most valuable mineral asset is guided by periodic negotiations with a private company. This is not an acceptable substitute for a vision. Unsurprisingly, with each negotiation the conclusion is that this time the deal is better. But how do successive administrations reach the conclusions?

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.