Inside the companies that operationalise agreements between Botswana and De Beers

Outlived their value or future icons?

– Sheila Khama

Oct 2023

Introduction

This is the first of four articles on Botswana’s diamond mining industry. My commentary focuses on the country’s main law governing mineral development as it relates to arrangements between the Government and De Beers Group. I provide an overview of Botswana’s legal and institutional structures and sequential highlights of the legal aspects of the partnership arrangements. Drawing upon accepted governance principles and sustainable development standards, I comment on what I believe works and does not work. In doing so, I am biased towards interests of the State and the interests of citizens of Botswana.

Background

This is the second of four articles on Botswana’s diamond industry. The first focused on the legal and institutional frameworks. In this article, I focus on the companies that were created in order to operationalize agreements between Botswana and De Beers over the development, sorting, valuing and marketing of Botswana diamonds. The Government of Botswana and De Beers formed and jointly own two such companies. The Debswana Diamond Company (Debswana) and Diamond Trading Company Botswana (DTCB) joint ventures (JV). Debswana is the mining entity and DTCB is the sorting, valuing and marketing arm.

I use my knowledge of corporate governance and governance of public institutions to provide a citizen’s perspective. I examine their mandates, governance frameworks, and operating structures. I examine the relationship between the partners, the companies, and the degree to which the companies are effective in fulfilling their mandates.

In addition, Botswana and Anglo American Corporation plc (AAC plc) jointly own De Beers Group. So, matters relating to this company too are the subject of my commentary.

Debswana Diamond Company

Debswana’s creation emanated from the Government’s legal right to acquire equity in mineral projects and was incorporated in 1969 under Botswana laws. The entity is responsible for operating four of the six diamond mines discovered by De Beers, namely, Jwaneng, Orapa, Damtshaa and Letlhakane. The remaining two discoveries were sold due to their economically marginal nature. Collectively the Debswana mines constitute the second largest diamond reserves discovered in the world since 1867 and since De Beers’ formation in 1888 in South Africa.

Diagram 1: Comparison of Debswana, De Beers and Alrosa Diamond Mines Reserves

As shown in Diagram 1 above and according to the 2022 S&P Capital IQ report on Botswana Metals and Mining Properties, the Russian company Alrosa has the largest reserves and resources at 1,176,454,000 carats, followed by Botswana at 941,468,400 carats. However, as illustrated in the diagram, if one adds the two De Beers mines in South Africa, the additional 271,430,000 carats result in total diamond reserves and resources of 1,211,889,400 carats, in which De Beers and Botswana have a measure of direct or indirect interest. This aside, in accordance with Botswana law, following the discoveries, the Government and De Beers negotiated and agreed terms of a partnership, leading to the development of the Botswana mines, production and ultimate sale of rough diamonds.

Equity Structure

At the time of the development of the Orapa diamond deposit in 1969 the minerals policy contained in the National Development Plan documents gave the Government a provision to acquire 15% to 25% carried (but not free) equity participation in any new mining project. Hence, the first important outcome of the negotiations about shareholding arrangements for the mine was the ratio of equity between the JV partners in the De Beers Botswana Mining Company as it was known. The equity was set at 85% to the investor and 15% to the Government. In accordance with the mining law, it was this company that was granted a mining license for 25 years to mine the Orapa/Letlhakane deposits. After the discovery of Jwaneng in 1972, and subsequent negotiations relating to the development of that mine, an agreement was reached between the JV partners to incorporate Jwaneng into Debswana. But the Jwaneng mine was granted a separate 25-year license. The discovery of the Jwaneng mine and the apparent size of the Orapa/Letlhakane production also resulted in an adjustment of the equity to 50:50%. This occurred in 1975, six years after the formation of the JV.

Development Costs

As part of the JV agreements, De Beers shouldered the financial cost of developing the first three mines, and the Government enjoyed carried interest while allowing the company an accelerated recovery of its mine development costs. At the time, the company had estimated that the recovery would take 7 years, but it turned out that the company had underestimated the deposit and was able to recoup costs in just 17 months. According to records, at the 1971 Orapa mine’s official opening, the development costs were estimated as ZAR21 million. (Botswana did not have its own currency, and this remained so until 1976). In the words of former President Mogae “De Beers contended that the project was marginal, its viability uncertain, was very expensive and given the company had to build every bit of mine and town infrastructure”. (https://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/interview-with-mr-festus-mogae-former-president-of-botswana-3235). In the field of mineral resource assessment, underestimation and overestimation are not unusual. Even more commonly, and to avoid the risk of financial underperformance, companies typically err on the side of caution. Equally, at the project stage, long-term resource estimates are accepted with the understanding that at the production stage, they will be progressively updated and adjusted to improve their accuracy based on increasing knowledge of the resources and reserves. At the project stage estimates are therefore used primarily to determine project economic feasibility.

Operators Agreement

Regarding the running of the mines, a technical services agreement (also known as an operator’s agreement) was entered into between Debswana and Anglo American Corporation of South Africa (AACSA) for the latter to operate the mines and provide management services to Debswana. This worked well for the JV partners because the country did not have the necessary workforce or expertise and so though theoretically, Debswana could have gone into the open market, the absence of a skilled workforce ruled out this option. The arrangement was also consistent with the AACSA corporate strategy across all its operations, including coal, gold, and platinum in South Africa. To benefit from economies of scale throughout the company’s supply chain, AACSA centralized corporate and technical support services, and only technical matters in diamonds were left to De Beers Diamond Services. In exchange, subsidiaries paid a fee to AACSA. From the perspective of the investor, the Botswana arrangements reflected this operating model.

However, critics of this corporate strategy argue that multinational corporations (MNCs) in partnership with others use it to their advantage, including transferring prices and imposing secondee executives whose loyalty is to one of the shareholders and not the JV that employs them. While the criticism may be valid, given limited expertise at the time, the suspicions would have been hard for the Government to prove. Once the production of diamonds and revenue increased a few years later (thanks to the Jwaneng mine output), the company’s capacity to sort and value large volumes led to the creation of a subsidiary of Debswana as a cost centre responsible for the sorting function. The company, which was established in 1982 and known as Botswana Diamond Valuing Company (BDVC), also relied on systems and technology developed by De Beers. Beginning in the mid-1980s, staff were brought from London to sort, while citizens were seconded to London for training.

Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs)

A major component of the 1969 arrangements was public-private partnership (PPPs) agreements under Botswana’s ‘sustained development’ drive of the first three decades of self-rule. According to the World Bank, PPPs are explained and rationalized as ‘a mechanism for government to procure and implement public infrastructure and/or services using the resources and expertise of the private sector.—-PPPs combine the skills and resources of both the public and private sectors through sharing of risks and responsibilities. This enables governments to benefit from the expertise of the private sector, and allows them to focus instead on policy, planning and regulation by delegating day-to-day operations.’

Based on this rationale, and in addition to mine-development infrastructure, by agreement De Beers also funded and managed public infrastructure projects for housing, water, electricity and multi-user schools, roads, hospitals and airports at the Orapa mine and town. In Jwaneng, the company built an airport and a hospital. While the airports are used to transport the product, ownership and operation of these airports is the responsibility of the Government. The hospitals serve as referral centers for Government-owned primary healthcare centers within a radius of 200 km. The Government supplies drugs while the mines administer, staff and fund running costs. Citizens use the hospitals on similar terms as public hospitals. In the late 1990s, the average annual outpatient visits for the Jwaneng hospital exceeded 20,000. However, the mine only had a staff complement of 2500. The large number relative to mine employees is made up of outpatients from communities near the mine. Another major contribution of the mines’ health infrastructure is that the hospitals have supported the Government’s containment of the HIV/AIDS and COVID-19 pandemics.

This deployment of PPPs has continued into the 2023 terms of the agreement to renew the Sales Agreement and four mining licenses held by Debswana. In its press statement De Beers stated as part of the arrangements the parties plan on ‘accelerating Botswana’s economic diversification through the creation of a multi-billion Pula Diamonds for Development Fund, with an upfront investment by De Beers of BWP 1 billion (c. $75 million). Further contributions over the next 10 years and will amount to BWP 10 billion (c. $750 million). The statement is not explicit but lack of mention of any contribution by the State must be interpreted to mean there will be no contribution by the Government. This is a significant financial commitment in a country in which the 2022 overall development budget of P 16.43b (about US$1,21b) for 2022/23 was a 11.4% Year-on-Year increase from a 2021/22 budget. As with previous PPPs, the fund will also be managed by De Beers – PowerPoint Presentation (grantthornton.co.bw). The arrangement is akin to the 1969 PPPs but speaks to current day development needs.

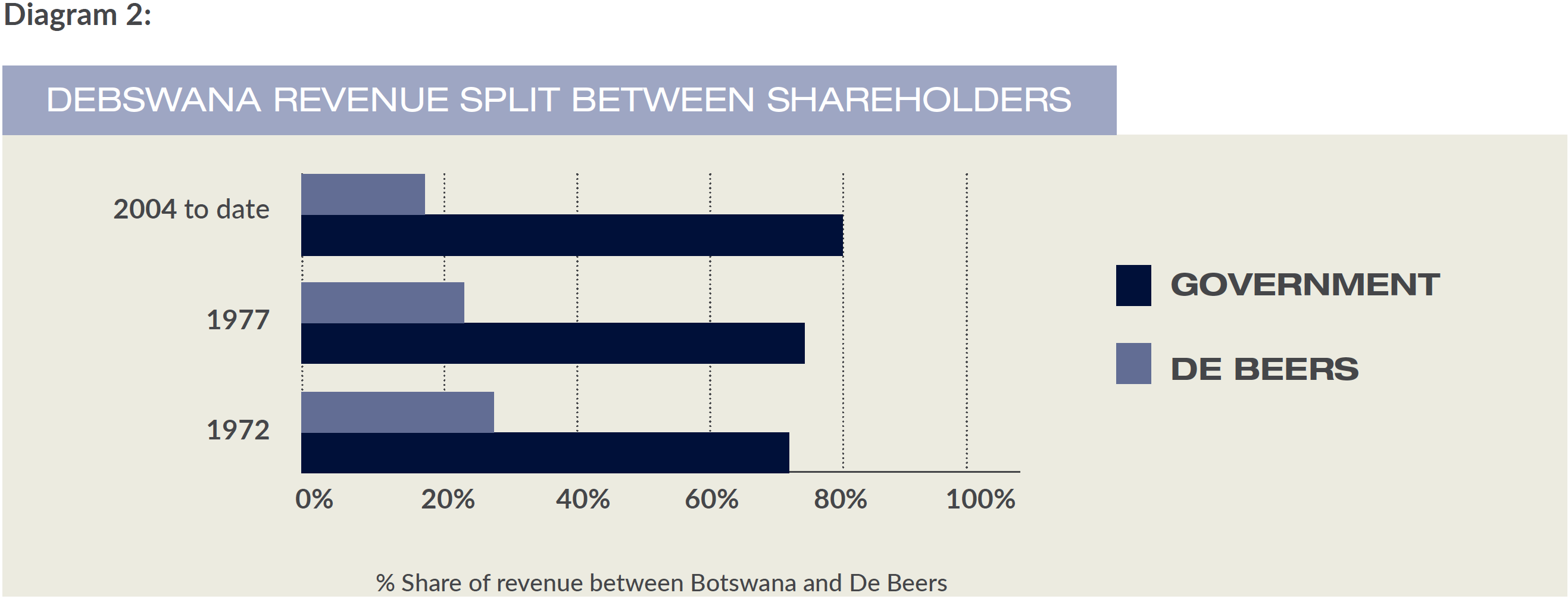

Split of Financial Distributions

From the start, the split in the percentage of financial distributions from Debswana favoured the Government and has progressively been adjusted upward following the revision of the terms of the agreements, but especially following the Jwaneng discovery. As shown in Diagram 2 below, the split has been adjusted three times, in 1972, 1977 and 2004.

The reason for the Government’s larger share, despite a 50:50 equal shareholding, is that in the eyes of the law, the Government is first among equals. It is entitled to different payments as the owner of the minerals and as the taxing authority. In addition, by law the payment of the monies is sequenced such that those going to the Government come first. As such the Government enjoys the combined benefit resulting from the sequencing and scope of payments. The Government receives royalty (rent for what is mined) and levies corporate tax on Debswana, both of which De Beers is not entitled to share. However, the shareholders split whatever dividends are declared by the JV equally, after the company retains sufficient income to fund future operations from free cash flow. But in addition to the dividends, De Beers earns a commission on the sale of the diamonds on behalf of the company albeit through De Beers Global Sightholders Sales (DBGSS). The Government also imposes withholding tax on De Beers share of dividends. For consistency, the distribution is adjusted as necessary to maintain the ratio at the current 80.8 to 19.2 percentage split.

Governance

To govern the affairs of the company, the JV has a board of directors composed of an equal number of representatives from the two shareholders. Until 2006 a De Beers representative chaired the meetings, but since that year, the chair rotates between the shareholders every two years. The role is purely for convening purposes and has no vote or decision-making powers.

What Has Worked

I have framed my observations and comments around the concept of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) and especially impact investing. The International Finance Corporation (IFC), which is the private sector arm of the World Bank Group, defines the concept of ESG as ‘an approach that aims to contribute to the achievement of measured positive social and environmental impacts. It has emerged as a significant opportunity to mobilize capital into investments that target measurable positive social, economic, or environmental impact alongside financial return.’

Return on Investment

Based on the initial investment made by De Beers and the Government, the financial returns have been very high, enabling Debswana to distribute multimillion US-dollar dividends every five weeks following the De Beers sales (sights). The exception was during the periods of major rough diamond market depressions of the 1983 and 2008 financial crises, leading to suspension of purchases from Debswana on grounds of force majeure (an unforeseeable circumstance that prevents someone from fulfilling terms of a contract). The impact of the diamond sales revenue on the economy is such that, diamonds accounted for about 20% of gross domestic product (GDP), about 80% of foreign exchange earnings and about 50% of Government revenues – (https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/412471468014434083/pdf/930490WP0P11940C00Botswana0Note04wc.pd).

Negotiating Capacity

Over the years Botswana development effective negotiating frameworks. According to public records, unable to fund all experts necessary to negotiate diamond mining arrangements in the 1960s and 1970s, Botswana received support from teams of experts provided by the Commonwealth Fund for Technical Cooperation, the Ford Foundation, and the Canadian Government. The experts augmented the country’s own team of civil servants and the few experts the country could afford. In time the negotiators were succeeded by the country’s Mineral Policy Committee (MPC). In addition, around 1982, under the leadership of Sir Ketumile Masire, Botswana procured the services of a London-based law firm called Slaughter and May. At the time, and by agreement, the senior partner responsible for Africa, Nigel Boardman, was responsible for the Botswana contract and retained the account even when he moved up in the firm as senior partner. By agreement Boardman, and not his staff, was physically present throughout all face-to-face negotiations, right up to 2011. Boardman is very well regarded by the fraternity and in business circles in and outside the UK. At least four times he was voted best legal strategist by The Times of London – (Star Dealmaker Nigel Boardman Leaves Slaughter and May After Nearly 50 Years | Law.com International). Because he advised mining, oil and gas companies all over the world, he used his experience and built a brand personally and for the firm. Therefore, he had much to lose reputationally by not performing well for his clients, and this, more than the money paid, was Botswana’s biggest insurance. By all accounts, it was a good and strategic decision by the Government.

Development of Human Capital

Debswana has successfully developed human capital through investment in tertiary education, in-house technical, vocational and skills training. Skills transfer in specialist fields has occurred between Debswana and De Beers operations upstream and midstream of the value chain such that by 1992, Debswana became self-managing, and the technical services contract with ACCSA was terminated. By 2023, the company’s scholarship programme had produced nearly 1000 graduates, and nearly 99% of all senior posts in the company occupied by citizens. From a diversity, inclusion and equity (DEI) perspective, by 2022, women constituted about 22% of the Debswana workforce. Debswana’s environment and conservation programmes meet global standards and the mines have been certified for compliance with the International Standard Organization (ISO). The company also has organized employee representatives with formal channels for engagements on worker rights. Details of other ESG standards and impact investing performance indicators can be found in the company’s report to stakeholders – (https://www.debswana.com/Media/Reports/DEBSWANARTS-2021.pdf).

Use of Technology

One of the most positive impacts of the Debswana JV is technology transfer through staff attachments and installations of technology in JV operations by De Beers research and development (R&D) units. As a result, Debswana mines are renowned for the use of advanced technology relating to diamond detection, sorting, valuing and security. The flagship is an installation designed by De Beers and Debswana engineers, known as the Aquarium, commissioned in 2001 – (FISH – State-of-the-art technology in final diamond recovery [journals.co.za]). The technology sorts diamonds without any human interaction and delivers them in sealed and tamper-free canisters from the mines to the sort house for valuation. It is the only one of its kind in the world. The technology has since been augmented with De Beers TracrTM platform which, according to De Beers, ‘brings together a range of leading technologies – including blockchain, artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things and advanced security and privacy technologies – to support the identification of a diamond’s journey through the value chain’ – (De Beers group introduces world’s first blockchain-backed diamond source platform at scale – De Beers Group). In an era of ESG, including a call for proof of provenance, this is the best evidence of responsible sourcing and proof that Debswana diamonds are not contaminated with illicit goods. This is essential for increasing demand. Other areas of extensive technology are comprehensive underground water management systems for conservation and the use of remote techniques to monitor rock stability for safety and avoidance of business disruption.

Free Integrated Sort House – A Section of the Aquarium – De Beers Group Technology [debtech.com]

PPPs Model

The use of PPPs to leverage De Beers financial and project management capabilities during the early stages of the partnership was expedient for the project and delivery of social services to communities, especially in the health sector. The referral hospitals enabled the State to invest in the provision of primary health care. In a keynote address at the launch of Vision 2016 Awareness Month on August 29, 2009, the Vice President of the country Gen. Mompati Merafhe said, ‘our health system has significantly improved over the years. Presently, 84% of the population is able to access health facilities within a radius of 5km while 95% is able to access health facilities within a radius of 8 km. Essentially, there are health facilities in almost every corner of this country.’ In the same breath, Debswana was the first company in the world to offer antiretroviral medicines to its employees and their dependents during and post-employment. The mine hospitals serve as blood banks for monitoring infection rates in collaboration with national authorities and are essential given the world’s vulnerability to health pandemics.

Driving Consumer Confidence

Diamond purchases are discretionary and thus vulnerable to public sentiment known as consumer confidence. Over the years, consumer confidence in diamond jewellry has been tested, and the image of Botswana as a stable democracy, with regard for rule of law, human rights and personal freedoms, has been a major ingredient in restoring it. This political climate and evidence of the country’s investment in the economic well-being of its citizens through PPPs, infrastructure, health and education have been invaluable sources of public assurance in main markets, including the US as a trend-setter. Specifically, Botswana’s image was used as evidence of the value of the industry in developing nations by its leaders and by the World Diamond Council during the 1999 UN conflict diamonds debacle and the bad press from the movie Blood Diamond. Botswana’s engagement at the UN and in the US Congress was pivotal in containing the risk of lasting damage when the US contemplated a ban on trade of diamonds. This reputation and De Beers knowledge of the market have been indispensable to driving demand. Speaking shortly before the US Congress passed the 2003 Clean Diamond Act, guaranteeing the way for imports of diamonds into the world’s largest market at the time, US. Senator Russ Feingold said, ‘Just two days ago I met with the President of Botswana. These states depend heavily upon their legitimate diamond industries to fuel economic growth. The states do not export conflict diamonds.’ If Botswana and its partners depart from practices that led to this sentiment, it will erode past achievements and open the industry and all those who depend on it to enormous risk. Therefore, for a country reliant on natural diamonds for its livelihood, good governance, rule of law and economic survival are not only a panacea, but they are inextricably linked. So far Botswana has nurtured the hand that feeds her.

Environmental Stewardship

Debswana sets high environmental standards in its operations including initiatives to reduce carbon footprint. They include installation of Replacement of Scrubbers with Pulping Chutes in metallurgical plants for processing ore to recover diamonds. A typical scrubber is driven by four (4), 75kW electric motors whereas the pulping chute has no moving parts thereby does not use any power.

When deemed necessary, the company has made up for the limitations of the law. For instance, although a mine decommissioning trust fund is not a legal requirement, the JV has established one to cover future mine decommissioning costs. The associated closure plans are updated annually for compliance with changing remediation standards and environmental conditions. Additionally, the trust fund is audited annually to ensure the funds can adequately to meet future remedial budgets. This decision was approved by the board of the JV. As with all aspects of the Debswana operations, relevant Government agencies are entitled to independently review the plans and books of accounts in order to satisfy themselves that the necessary environmental protection interventions occur on an ongoing basis and that future plans and financial resources are adequate to meet project decommissioning costs. As such from an ESG and impact investing perspective, it would be hard to find Debswana non-complaint.

What COULD BE IMPROVED

Forward-Looking PPP Arrangements

It is understandable that in the early days of the relationship, negotiations with De Beers focused on revenue from Debswana and provision of social services. However, in time an opportunity was lost to go beyond infrastructure PPPs in the vicinity of mining projects. Specifically, given that part of De Beers core expertise is infrastructure project design and execution, more could have been done by the Government to leverage the expertise and to transfer skills to relevant public institutions. In a country and region in which public projects cost overruns and poor delivery are commonplace, more effort could have been made to tap into De Beers expertise and to foster a culture of efficient public projects delivery, thus avoiding public revenue waste. Reports of public projects cost overruns suggest that Botswana is in dire need of project governance systems and execution capability. Collaborating with De Beers whose track record on the Debswana mines is just the opposite, the experience might have provided the Government the right foundation to build institutional capacity and discipline. A public infrastructure projects coordinating system akin to the UK’s Infrastructure Project Authority – (Infrastructure and Projects Authority – GOV.UK [www.gov.uk]) could serve as a model.

Research and Development Capabilities

In most aspects of upstream and midstream diamond value chain, R&D projects are core to De Beers competitive strategy, and the company invests millions of US$ to maintain its technological leadership. The outcome is that the company’s capabilities in geoscience, mining engineering, product security, sorting, valuing and synthetic detection are unparalleled. To improve efficiency and give the companies a competitive edge, the products and systems are deployed in Botswana, Canada, Namibia, South Africa and Ireland in onshore and offshore operations as well as open and underground mines – (Technology – De Beers Group https://www.debtech.com/).

In this respect, the company’s Centers of Excellence and R&D laboratories are logical partners for Botswana universities and research institutions. But for at least the first 40 years, there was no effort to leverage the opportunity. At the initiative of De Beers Botswana and Debswana, in 2009 an effort was made to entice the University of Botswana, resulting in an MOU. Beyond that there was no traction, and the opportunity cost is immense. Though very successful, the UB Okavango Research Centre, opened in 2002 and funded by Debswana, De Beers and the Oppenheimer family, was a CSR initiative and not embedded in diamond technology. As such it does not meet the criteria for development of technology-driven capabilities.

Mine Closure Laws and Regulations

Botswana is a mining dependent economy and thanks to demand for metals critical for the industrial north’s transition to clean energy, more mines are likely to be commissioned in the country. But Botswana’s laws lag behind in making provisions for mine closure to mitigate adverse effects on the physical and social environment. This needs to change.

Diamond Trading Company Botswana (DTCB)

In 2008, another 50:50 JV between Botswana and De Beers, known as the Diamond Trading Company Botswana (DTCB), was incorporated under Botswana laws. The company replaced BDVC, and it sorts and values Debswana production for sale. Under a 2006 agreement, and unlike BDVC, DTCB is a standalone entity and not a subsidiary of Debswana. However, as was the case with BDVC, all sorting, valuing, sales systems, processes and technology are designed and supplied by De Beers under license to the JV. Regarding the sorthouse, the cost of the land, construction and equipment of US$85m and was borne by De Beers. The building is nevertheless owned by the DTCB and upon its completion, De Beers estimated the value of the property alone at about US$290m.

As part of the Government’s goal to promote cutting and polishing of diamonds in Botswana, an additional mandate of DTCB was to be an agent of DTC International (now DBGSS) to sell 10% of aggregated diamonds to factories licensed in Botswana. This meant that De Beers remained the sole buyer of Debswana supply and that the factories received aggregated parcels of diamonds from all De Beers operations and not Debswana only. Although small relative to Debswana revenue, DTCB’s source of revenue is a sales commission from the sales of Debswana goods to De Beers. The dividends from profit are split equally between the shareholders. The shareholders have an equal number of seats on the JV board, and the chair rotates between the two every two years. The chair has no voting power.

What Has Worked

Cutting and Polishing Industry

DCTB has successfully contributed to the growth of a local cutting and polishing industry by facilitating the supply of Botswana-based companies before De Beers relocated its UK distribution based function to Botswana in 2011. The number of factories has increased from the first 10 in 2008 to 16 in 2009, and in 2023 this figure is 38 factories. At the same time, the annual value of the rough diamonds sold to the local factories at year end 2022, was US$950m, with over 3500 jobs created.

Skills and Technology Transfer

DTCB employs 450 citizens originally trained by De Beers in London to sort and value diamonds using the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) standards and De Beers systems and technology. The company has successfully transferred skills, such that unlike in the 1980s, when Botswana production was sorted by employees from the De Beers UK office, by 2004 up to 95% of employees were citizens and today the company only employs a workforce of citizens sorters. In addition, the sorting equipment is operated and maintained by citizens, and the company has an in-house training academy. An important contribution made by the technology is that some machines sort stones that would otherwise be too small to cost-effectively process by hand. Even if the company were willing to sort the stones manually, the time it takes to sort would be too long to complete within Debswana’s six-weekly run of mine production volumes. This would interrupt the six-weekly Debswana sales and revenue payments to the shareholders. The alternative might be to leave the diamonds on the tailings dump on the mine site, as was the case before the automated sorting machines were available. This would have rendered the diamonds redundant, at least until a solution was found. In terms of time value of money, this would undermine the investment made in mining the stones.

Product Security

Botswana laws and law enforcement agencies, BDVC, DTCB and Debswana diamond security systems, have secured the country’s diamond wealth for 50 years with few incidents. Internal and external processes pertaining to handling of rough diamonds in Botswana also ensure that any illicit trade does not contaminate Botswana diamonds. This and De Beers blockchain technology being developed will continue to ensure proof of provenance and strengthen the Kimberley Process’s chain of custodianship whose credibility was brought into question following to the controversy surrounding Zimbabwe membership.

De Beers Group Partnership

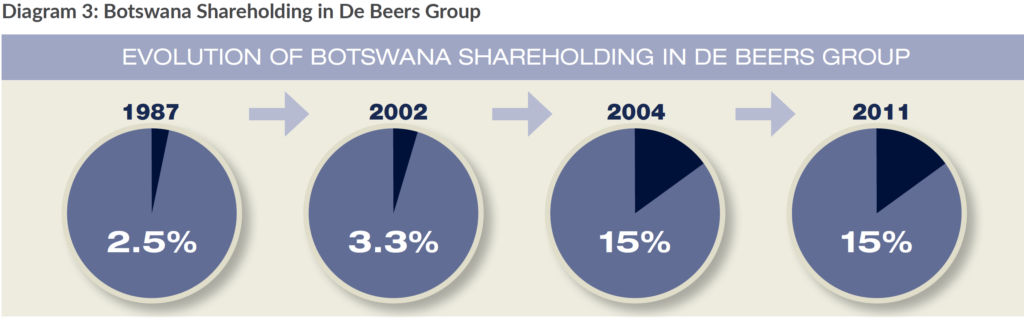

The third JV is De Beers Group. The company is registered as De Beers Centenary Société Anonyme (DBSA) in Luxembourg and is governed by sovereign and EU laws. It holds the shares in Debswana and is owned by AAC plc and the citizens of Botswana, with an equity ratio of 85:15% in favour of the former. The Government’s original acquisition of the shares was a result of a protracted rough diamonds price drop during the 1983 recession. As per provisions of the agreement with Debswana, De Beers suspended purchases from Debswana during the recession in order to avoid selling diamonds cheaply, including the Debswana production. But to protect jobs, production continued and Debswana stockpiled. When the market recovered, De Beers did not have the cash flow to purchase the entire stock. So, De Beers proposed an exchange of a stock of Debswana diamond for shares instead.

This was agreed, and Debswana joined AAC plc and the Oppenhiemer family as a shareholder. Over the years, the company’s equity structure has undergone several changes, but as shown in Diagram 3 below, in essence it evolved such that in 1987, De Beers issued 5% equity to the Debswana JV, which amounted to an effective 2.5%, equity to the Government. The shareholding afforded Debswana two seats on the board, and from the beginning the seats were allotted to representatives of the Government. In 2002, the equity increased to 7%. In 2004, it was increased to 15% and transferred to the Government, while the board representation remained unchanged.

The result was that De Beers had three shareholders, namely the Oppenheimer family, who owned about 40% of the company, AAC plc with 45% and Botswana with 15%. When the Oppenheimer family-owned company sold its interest in DBSA in 2011, AAC plc and Botswana had the right of first refusal to acquire the shares. Botswana opted not to increase its shareholding and effectively gave AAC plc a controlling share, resulting in the current shareholding of 85:15% in favour of AAC plc.

What Has Worked

Additional and Future Income

The agreement between Debswana and De Beers to swap diamond stocks for equity was strategic and is financially valuable for Botswana and Debswana. For instance, when the company was delisted in 2001, it was valued at US$16b. Depending on how the partners leverage it, it was and remains potentially transformational. The transfer of the entire equity from Debswana to the Government in 2004 was momentous. It provided the Government with an additional and future source of revenue when Botswana diamond mines close. In the interim, additional revenue from discoveries by De Beers elsewhere in the world, would augment revenue from Debswana. In sustainable development terms, Botswana successfully invested its mineral for the benefit of future generations by investing Debswana diamonds to meet future needs.

Strategic Leverage

The seats allocated to Government representatives on the board of directors broaden the Government’s potential influence and understanding of the business and De Beers strategies in relation to Botswana entities and competitors. This influence and understanding enables the Government to mitigate risk of any adverse impact of strategies and decisions taken by the De Beers board and executives on arrangements with Botswana and on the country’s own national development goals. It is an enormous opportunity to transfer industry commercial knowledge and skills to public officials, given the asymmetric nature of capacity between private investors and governments. It also offers an opportunity to build trust between the investor and the Government. A pre-condition is that the Government seizes these opportunities.

What Could Be Improved

Increasing Shareholding

Botswana’s decision not to exercise the right to acquire a portion of the shares relinquished by the Oppenheimer family company, on grounds of lack of internal liquidity, was ill-advised. Lack of cash resources is understandable following the 2009 crisis. However, a cash payment was not the only option. An obvious option was a shares-swap to give De Beers a larger stake in Debswana, such that while Botswana’s shares in Debswana reduced, they increased in De Beers. From a return-on-investment perspective, although the former is not as profitable as Debswana, it is one of AAC plc largest sources of income. De Beers’ additional equity in Debswana would have increased that company’s profitability and with it the Government’s dividends from De Beers. The deal could have been structured to compensate for the reduction of Debswana revenue. Importantly, the move would have guaranteed future generations a greater share of revenue in De Beers. From a sustainable investment perspective, this is an important consideration because it secures future income for a country whose own diamond resources are declining and where economic diversification has been elusive. By contrast, De Beers continues to search for deposits in other regions including Angola, which has significant geological potential.

Leveraging Seats on the Board

The single most important role of any corporate board is strategic oversight, and for more than 30 years the Government has had two seats on the board of De Beers. Yet there is little evidence of how the Government capitalizes on this access to be able to influence strategy at the highest corporate governance level so that the company’s decisions are aligned to national interest. Instead, to align interests and/or create a level playing field, the Government waits for negotiations of mining licenses and sales agreements at intervals of 25 years and 10 years, respectively. This means the Government is addressing long-term strategic matters transactionally. Yet to be effective, the matters should be dealt with in such a way that by the time the partners revisit interim agreements relating to the Botswana registered JVs, De Beers shareholders have achieved full alignment, and the agreements are structured to merely reflect this.

Specifically, the approach, in which the two shareholders negotiate as if they are not negotiating over policies of companies they jointly own, defies logic. It is a fundamental failure in corporate governance as relates to the role of a board to guide strategy and protect the interest of the shareholders—the citizens of Botswana. It is a three decades long fundamental failure on the part of the public officials charged with the fiduciary responsibility and of their principals for not holding them to account.

Protecting the Investment

As one of the shareholders, in 2008 Botswana contributed US$83m towards a shareholder loan and proportionate to its equity. This followed the 2008 crisis in which the world financial markets collapsed at a time when De Beers needed to proceed with future mine projects. In addition to the original investment, such additional financial contributions and the value of Botswana’s 15% stock in De Beers should not only be protected it should also be enhanced at every opportunity. But one gets the impression that there is a complete indifference towards the citizen’s ownership of equity in De Beers. There does not appear to be an understanding that a weakened De Beers erodes past and future investments by Botswana in the company.

On the other hand, over the years Botswana’s image has rebranded De Beers away from the company’s historically negative South African mining legacy. Botswana should harness that value and not devalue its own achievements. Acting contrary is a bizarre own goal. Importantly, over the years, Botswana’s disinterest in protecting equity has opened the door for De Beers competitors, who undoubtedly recognize the naivety and use it to their advantage to turn Botswana into a weak link in the partnership. But the long run impact of these actions are on the country and its people and neither De Beers nor the company’s detractors.

The above seems to contradict Botswana’s conscious understanding of this strategic imperative. On the day of the signing of the 2006 landmark agreements and in a written speech intended for Parliament, the Minister of Minerals, Energy and Water Resources Mr. Charles M Tibone said, ‘I must remind you that the Government of Botswana has shares in De Beers and that as such we strive to strike a balance between the interests of the Botswana subsidiaries with those of Botswana in the De Beers Group. Therefore, care has been taken to ensure that nothing contained in these agreements undermines Botswana’s current and future investment return in the partnership.’ This is vital, but the absence of clearly laid-out parameters and guidelines to ensure that this principle of paramount importance is abided by, in advance of other strategic decisions, places the goals espoused in the Minister’s statement at risk.

Marketing Expertise

Much can and should be done to market the country and brand it suitably, leveraging De Beers marketing expertise. Marketing of a luxury commodity is De Beers mainstay. Between dependence on diamonds and high-end tourism, Botswana’s economic livelihood straddles two prominent luxury industries. The two appeal to the same consumers and therefore complement each other. In high-end tourism terms, Botswana’s Okavango Delta exists in the shadow of significantly less attractive regional destinations due to less aggressive marketing and visibility. As a result of recent bad press, (thanks to the squabbles in the ruling party) and reports by third party governance watchdogs, in the long run Botswana could lose tourists to other SADC countries. The need to collaborate with its partner De Beers to restore its reputation has never been more urgent. This is an inherent advantage of being a shareholder and the recent announcement of a fund to help with branding is therefore welcome.

Centralized Decision-Making

Despite the level of materiality of many of the transactions mentioned, the decisions above were taken without consulting Parliament or the public. This falls short of good governance as relates to accountability and public participation. Confining decisions on a matter of intergenerational impact to the Executive Branch, while excluding Parliament and civil society, goes against current governance norms and ESG principles. It places Botswana in the category of the institutionally unprogressive.

Stakeholder Engagement

A review of company websites shows that the level of reporting and engagement varies. De Beers website contains more information, including financials. This is to be expected, given laws where the company is registered and the fact that the main shareholder AAC plc is publicly listed. The content of the Debswana website reads, ‘Debswana is a private company and does not publish its financial statements.’ So, although the company routinely produces useful information it is nevertheless incomplete because it does not contain financials. The rest of the information is contained in the company’s Report to Stakeholders – (Welcome to Debswana). DTCB has the least amount of information – (DTC Botswana – Pride and Prosperity through Diamonds). Viewed collectively, all three could engage more proactively and transparently with citizens. Though these expectations are higher in the case of listed companies, the fact that the three companies above have citizens as shareholder makes disclosure and engagement just as important.

Exploration Partnership

One of the provisions of the June 30, 2023, principle agreement is that Botswana enjoys right of first refusal as a partner with De Beers in international exploration projects. De Beers and Botswana will launch an international diamond exploration partnership to discover new diamond sources. The new partnership will seek opportunities in and outside Botswana. Additional details may well nullify this comment but taken on face value for both Botswana and De Beers, it appears counterintuitive because by virtue of the De Beers Group shareholding, and simplistically speaking Botswana already has an interest in such activities. Any investment would be a duplication and unjustifiable use of public coffers.

Conclusion

As can be seen from the above, much has been achieved, but there is also plenty of room for improvement. Two matters that require greater attention are increased disclosure of information to stakeholders and greater alignment of strategies between the shareholders and across the three companies. It is through government policy and governance mechanisms of the companies that the matter should be pursued. Taking a matter of the country’s livelihood into the political arena will not serve the relationship between the partners and even less the people of Botswana. For De Beers, asserting the rights of the company, given the level of investment in Debswana and DTCB, is a more credible stand than hoping precedence will prevail. For both parties, working together rather than separately, the shareholders of the three companies and the operating entities themselves are likely to be more effective in protecting public interest and securing consumer confidence than otherwise.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.