Botswana State Owned Enterprises and Diamonds

Champions for development or business as usual?

– Sheila Khama

Nov 2023

Introduction

This is the last of my four articles on Botswana’s diamond industry. The first addressed policy, legal and institutional frameworks, while the second focused on the operations of joint ventures (JVs) between the Government and De Beers. The third examined Botswana’s quest for value addition and the impacts of it on marketing arrangements between Botswana and De Beers. In this article, I turn my attention to State Owned Enterprises (SOEs). I review the governance of the SOEs and their potential to contribute towards value addition given their mandates and government policy goals.

In many countries SOEs in mineral, oil, and gas industries dominate economies but their performance in governance and investment terms varies. In some countries, they are spectacularly successful and have transformed national economies. In others, they have been a colossal failure draining national coffers while benefitting political interests. Having not had an SOE in the diamond industry for more than forty years, in the last decade Botswana joined the ranks and created its own diamond marketing SOE and a mineral investment holding company. These are the Okavango Diamond Company (ODC) and Minerals Development Company Botswana (MDCB). Given the ages of the two SOEs, the jury is still out on where they fit in performance terms and so, the commentary assesses the journey so far.

(https://www.odc.co.bw/)

ODC was incorporated in 2013 as a private company. This separates ODC from most other Botswana SOEs that were created by Acts of Parliament in that the former is governed by company law and related principles of corporate governance. The board of the company is appointed by the Cabinet upon recommendation from the Minister of Mineral Resources, Green Technology and Energy Security (MMGE). Both the Minister and the Cabinet represent the Government which in turn is the agent of the public. Under company law, the company, its board, and its directors are independent entities with legally protected powers and rights separate from the Government that appoints them. As articulated by one governance watchdog, ‘as an agent of the company, a director owes two basic duties: to exercise his powers in good faith in the interests of the company, and to act with reasonable care and skill.’ – Review of business laws in Southern Africa. – Part 6 (fes.de).

This means the board has full legal and delegate powers to preside over the strategy of the company and to act in the interest of the company and neither itself nor the Government of the day. In this respect, the board individually and collectively is answerable to the shareholder for its exercise or failure to exercise these powers. By implication, in corporate governance terms, there cannot be any interference with the work of the board nor should the board subject itself to such interference. These are important factors when considering the governance of the SOEs in which there can be a risk of political overreach.

Historically, the creation of ODC followed the conclusion of interim negotiations to renew the Sales Agreement between De Beers and Botswana in 2011. One of the outcomes of those negotiations was an agreement to set aside a portion of Debswana production for sale to ODC. This essentially introduced the provision of a Production Sharing Agreement (PSA) between De Beers and Botswana. This is unusual in mining albeit common in the petroleum industry because crude is traded as a commodity and third-party offtake agreements are commonplace. However, a PSA enables the host country to maintain some control over mineral production through the SOE share. In Botswana, the aim of the PSA is to enable ODC to independently auction diamonds. According to the company website, ODC’s mandate is, ‘to provide the Botswana Government with a direct route to market for its rough diamonds and to support the ongoing transformation of Botswana into a leading rough sourcing destination.’ ODC defines its target market as, ‘a broad and diverse customer base and any company that is active in the diamond supply chain and shares our ethical standards can apply to become an ODC customer.’

Another objective of ODC is price discovery, and the ability of the company to secure product pricing intelligence and avail the information to the Government based on records from sales. ODC ended a decades long set up in which the company relied exclusively on De Beers for such know-how. The rationale was that the market knows the value of diamonds better than a company and that an auction system would generate a market clearing price from competitive bidding. The premise was that in strong market cycles, auctioning would yield higher sales turnover, but in weak market cycles De Beers contracts would perform better. Though not stated, implicitly, through increased industry knowledge and changing national aspirations, ODC potentially lays the foundation to self-determination. It is worth noting that, so far, on matters of value addition and PSA, the Government has only targeted Debswana, and not the other diamonds miner, Lucara Diamonds which sells all its production in Antwerp. – (https://lucaradiamond.com/).

ODC started its trading activities in 2013 at which point its share of production was 12% of the value of Debswana goods and progressively rose to 15% in 2016 and 25% in 2020 where it remained till June 2023. Originally, ODC auctioned Debswana diamonds online. But ODC sales are now conducted through inperson auctions but bidders are nevertheless subject to the company’s vetting process. At the start, ODC struggled to get on its feet but following a decision to move from online auctions to in-person events, the company has been successful in generating significant revenue for the country. For instance, in the last two years, ODC’s annual sales were about US$1b. The question is how this compares with De Beers’ sales in the short and long term and for that matter during times of high and low demand. An equally important question is the impact of auctioning on the stability of public revenue given that unlike De Beers contracts, sales through auctions are not guaranteed.

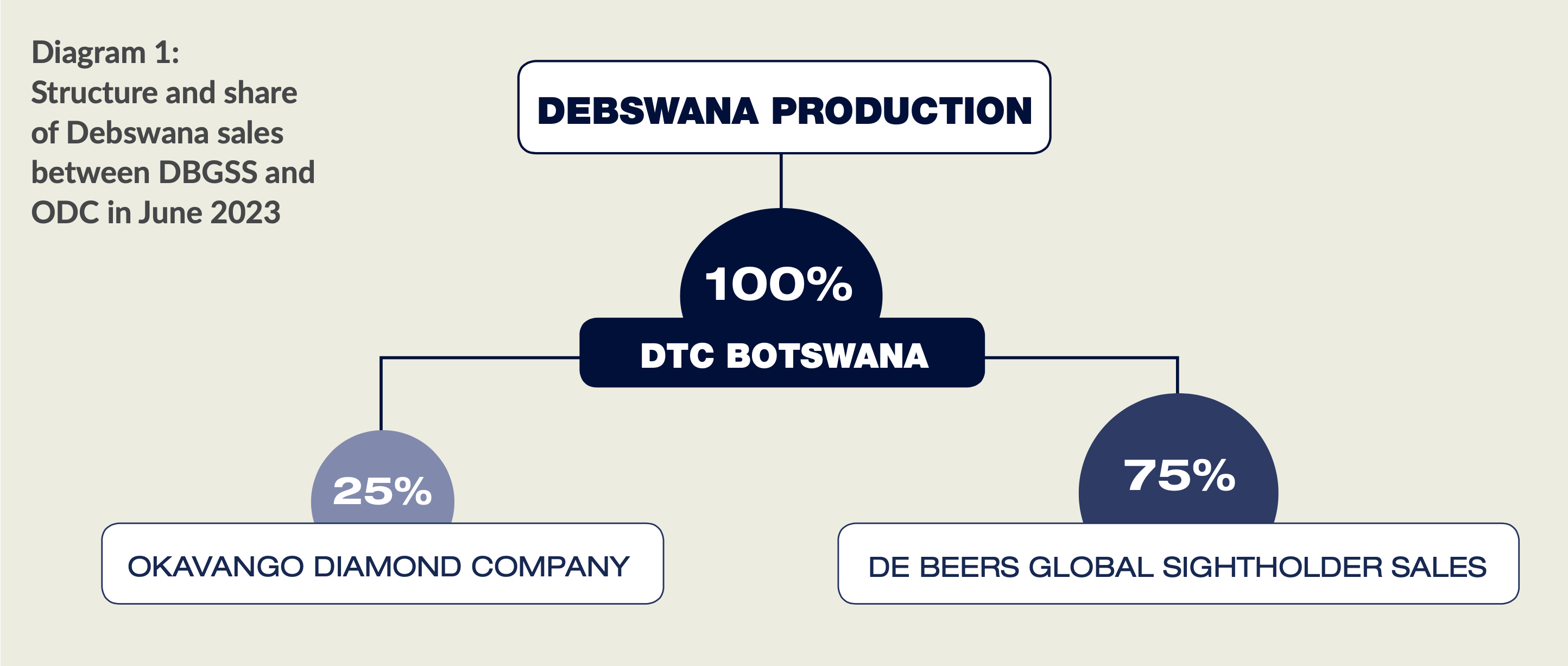

Implications and Impacts of ODC on Botswana’s Rough Diamond Market

The company’s marketing strategy introduced a number of changes to the marketing of Debswana production and impacted De Beers’ business model. To start with it reduced De Beers’ market footprint. Secondly, it introduced unaggregated Botswana diamonds into the market. On the other hand, starting with the 2011 arrangements, the creation of ODC meant that between the company, De Beers Global Sightholder Sales (DBGSS) a wholly owned subsidiary of De Beers and Diamond Trading Company Botswana (DTCB), the Government had direct and indirect equity in three separate entities, each marketing rough diamonds to different clients, through different channels and under different terms and conditions. This also means that two of the companies (ODC and DBGSS) compete with one another for Debswana supply and clients. Diagram 1 depicts the resulting diamonds distribution structure and the percentage share of Debswana diamonds between DBGSS and ODC from 2013 to June 2023.

An important difference between the DBGSS and ODC is that the latter only markets Debswana diamonds, while De Beers sells aggregated goods using production from Botswana and other countries in which the parent company operates. Importantly, arising out of the 2011 and 2023 Sales Agreements, ODC is not obliged to supply Botswana-based diamond cutting and polishing factories. That is to say, over this ten year period, ODC client were at liberty to cut and polish the goods outside the country. This is in contrast to DBGSS because following the 2006 and 2011 agreements, the company was obliged to supply a portion of its aggregated goods to Botswana cutting and polishing factories and this has continued to date. The value of DBGSS goods supplied to Botswana factories in 2022 was US$950m. Following the conclusion of the June 2023 negotiations, the Government committed ODC to supply citizens. More recently ODC also announced plans to supply foreign-owned cutting and polishing factories already operating in Botswana. This ticks many boxes except it does mean much of ODC’s share will still be exported rough and so one might argue that this undermines the Government’s value addition goals.

Given ODC’s objective of price discovery, one would assume that systematic evaluation of the company’s performance relative to De Beers is an essential part of its performance measurement frameworks. Among others, the assessment would enable the Government to determine which system performs better between auctions and contracts (or for that matter an appropriate combination of both). Equally, the assessment would enable the Government to determine whether the strategies of the three companies in which it has a stake are complimentary. Importantly, the exercise would enable the Government to satisfy itself so that in the end and all things considered, the economic sum of the parts is verifiably greater. The buildup towards the negotiation of the renewal of Debswana Sales Agreement which started in 2022 was an ideal opportunity to conduct such an evaluation of ODC’s performance. It would have offered a baseline for the next PSA. However, so far, there is no record of such an exercise being undertaken since ODC’s establishment.

2023 Renegotiations of the Sales Agreement Strategy and Process

HB Antwerp Negotiations

The 2022 negotiations for the renewal of the Sales Agreement took place simultaneous to those between Botswana and HB. The latter negotiations revolved around the company securing supply from Botswana and setting up a factory in the country. Though it is not unusual for companies to approach Botswana for supply of diamonds, the discussions have typically been aligned to existing arrangements with De Beers including the timing of conclusion of the sales agreement between Botswana and De Beers. Given that ODC’s share of supply is an outcome of agreements between Botswana and De Beers, the arrangements naturally lay a foundation for ODC’s supply agreements with the company’s own clients.

On the other hand, all Government negotiations with mining companies have been conducted by the Mineral Policy Committee (MPC). According to the 2022 Mineral Policy, the MPC is responsible for ‘advising the Government on mineral strategic matters.’ However, in the case of HB, a separate team was specifically constituted. Furthermore, the board and management of ODC were not party to the negotiations with HB. Neither was the Diamond Hub which is ‘responsible for downstream development of diamonds’. The decisions are inconsistent with institutional arrangements and policy and is highly irregular from a corporate governance perspective. Importantly they undermine the Government’s own stated policy and institutional frameworks. As such, they deviate from principles of good governance. – (https://bgi.org.bw/sites/default/files/Botswana%20Minerals%20Policy%202022.pdf).

HB Antwerp Arrangements

The above notwithstanding, in March 2023, the Government and HB announced that an agreement had been reached to partner such that Botswana acquires 24% equity in the company for an undisclosed sum. In the same announcement the parties reported that HB had secured an agreement with the Government to be supplied diamonds through ODC and not DBGSS as is the case with other cutting and polishing factories. No details of how the 24% equity was determined or valued were made public. But unless provided on an extraordinary basis, this would normally mean that the percentage is just 1.5% short of the Government having a seat on the board and would therefore mean the five other shareholders control of the company. Put another way, through the PSA, the Government strengthened its position relative to De Beers. Simultaneously and in relation to HB, the Government opted to pay for equity but weaken itself by settling for a minority stock while guaranteeing HB supply of ODC’s quality stones outside the SOE’s auctioning business model at the time of announcing the arrangements.

In his address at an inauguration event of HB’s Botswana subsidiary during the same month, President Masisi said, “The HB Botswana facility in Botswana is the realization of close collaboration and partnership between the Government of the Republic of Botswana and HB Antwerp. We are forging a brighter future for the next generation of Botswana, taking unprecedented ownership over our natural resources to realize their potential for our nation’s sustainable development.” – (HB Botswana – HB Antwerp). Questioning the governance process relating to the equity financing arrangements in June 2023, the Member of Parliament Mr. Saleshando asked the Minister responsible to inform parliament on how the stock purchase would be funded given that there had been no provision for the acquisition of the shares in the National Budget announced in February 2023.

The Minister contradicted his principal and responded by saying that no agreement had yet been reached with HB. – (https://www.finance.gov.bw/images/speeches/Minister/2023BudgetSpeechDocs/2023_Budget_Speech_06_February_2023.pdf). Though lacking in details, the company’s Botswana subsidiary confirms the arrangements. – (HB Botswana – HB Antwerp). No information has been made public on how HB was selected or why the Government opted to acquire equity in HB and not any of the other factories operating in Botswana since 2006.

Since these developments, more colour has been added to the HB storyline and on September 11, 2023, HB announced that the company had removed the managing partner from his role but that he remained a shareholder. – (HB Antwerp co-founders clash over gem trader’s future as Botswana deal looms | Reuters). In response Mr Oded Mansori, issued a press statement vowing to fight the matter in court. On September 27, 2023, HB’ supplier of diamonds Lucara Diamonds issued a press statement to the effect that the company had terminated its supply agreement with HB following the client’s material breach of the contract. – (https://www.bloomberg.com/press-releases/2023-09-28/lucara-diamond-corp-announces-termination-of-diamond-sales-agreementln2gy3kh).

In a quick turnaround in October 2023, HB announced that the partners had reconciled their differences with Mr Mansori. On being asked about Botswana’s position given the state of affairs, The President of the country indicated that no formal agreement had been signed and that the Government was considering the matter. In his State of the Nation address on November 6th 2023, The President said, ‘Mister Speaker, allow me to state before this house that, in March 2023, Government made a pronouncement to the effect of purchasing a 24 percent stake in HB Antwerp. I am happy to announce that due process of detailed, legal and commercial due diligence is now ongoing to finalise the deal.’ The sequencing does not sound right because due diligence is not meant to finalize a deal but to determine whether a deal should be entertained in the first place.

2023 Negotiations Outcomes

Going back to the negotiations with De Beers, on June 30 2023, Botswana and the company announced a principle agreement for the renewal of the Debswana mining licenses and the Debswana Sales Agreement. Regarding the latter, the announcement stated that Debswana would immediately increase supply to ODC from 25% to 30% of production. Further that by the end of the 10 year period of the agreement in 2033, supply would have risen to 50%. What was missing in the announcement was an explanation for the incremental rather than immediate increase. However, in a later report Reuters quoted, the Managing Director of ODC as saying that; “ODC auctions are too big and need to be optimized,” ODC Managing Director Mmetla Masire reportedly added that “We also need to de-risk the business and support other customers that want alternative selling channels. While ODC is not moving away from the open tender model, the new channel should complement and work in parallel with auctions.’ The approach makes logical sense given that ODC would double its volumes. Therefore, the company presumably wants to ensure operational readiness.

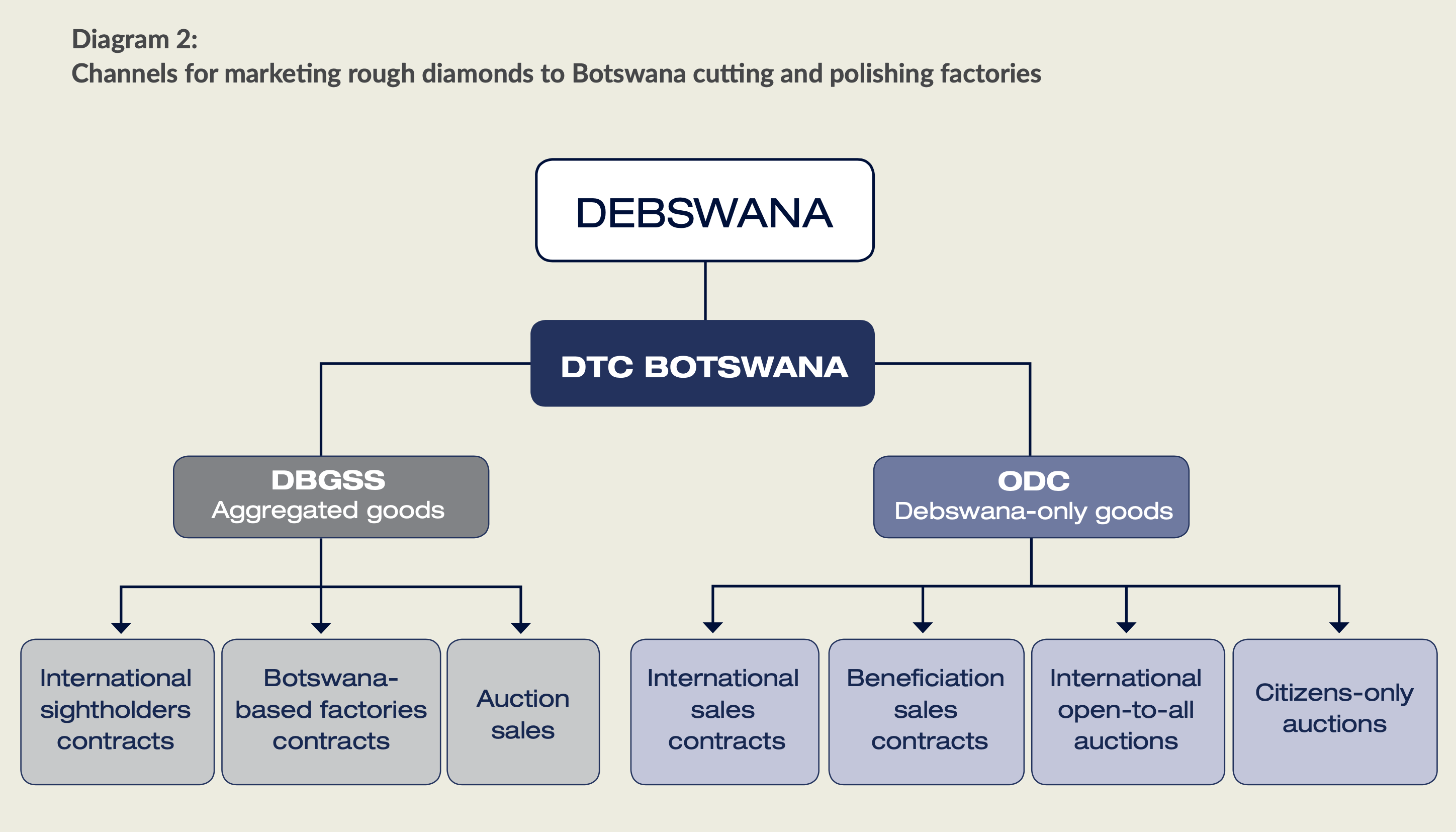

Following conclusion of negotiations with De Beers, the Government also announced that ODC would supply citizens in possession of Precious Stones Dealers Licenses (PSDL). Since then, ODC shed more light on the matter. In essence, a decision has been taken for the company to supply citizen entrepreneurs and it will set aside a small portion of its stock (the value has not been specified) for this purpose. But this is not all, ODC will also add a third channel to its distribution network by also entering into sales contracts with cutting and polishing factory owners based in Botswana and a fourth one being contracts with international buyers. To serve citizens, ODC will create a new sales channel such that citizens can purchase diamonds through a separate auctioning process to the existing one. The citizens-only auctions will avail smaller lots of about a quarter of the standard ODC auction lots. The reserve price will not be discounted but arrived at by using normal open ODC auction processes. To qualify to participate, the bidding company must be owned by a person holding Botswana citizenship, in possession of a PSDL, and be registered with ODC. The main goal is to assist in developing a cadre of citizen diamantaires by giving Batswana access to rough diamonds in 2024. This means in the end citizens can participate in all the four ODC sales channels of, (1) citizen only auctions, (2) international auctions, (3) fixed international sales contracts and (4) fixed beneficiati on sales contracts when both commence. At this stage ODC does not concern itself with whether the goods are manufactured in Botswana or exported except for category 4.

Regarding supply to Botswana-based cutting and polishing factories by DGBSS, the 2023 agreements provide that De Beers will increase the value of supply from US$950m to US$1b annually. The quantum is low in comparison to the one agreed in 2011. At the time the increase rose from US$550m to US$950m by 2022. No doubt this is because the company is getting less supply of diamonds from Debswana. Presumably category 4 of ODC’s distribution channels bridges this gap though the value is unknown since unlike De Beers, ODC does not disclose these details and other financial data. But in this scenario, the losers are clearly the existing factory owners who invested in Botswana, and the winners are newcomers like HB now guaranteed special stones by agreement and potentially citizens ringfenced against foreign competition while able to participate in all other channels. Either way, the policy direction is becoming increasingly multidimensional as Botswana departs from the 2006 arrangements in which cutting and polishing was the primary vehicle for value addition. Focus appears to have shifted to PSA, citizen empowerment, and revenue generation.

Dubai Multi Commodities Centre

Debswana Diamonds Distribution Structure

As shown in Diagram 2 below, put together these developments mean that operationally, rough diamond sales arrangements for the Debswana production have progressively become complex.

The diagram shows that in addition to being a shareholder in three companies in Botswana through which Debswana diamonds are sold, the Government has added different clients and different systems to ODC’s business and operating models.

While the complexity in monitoring of the various State interests is not insurmountable, it nevertheless increases operational risk and the need for additional internal and external oversight. Botswana and De Beers recognize the complexity of the market environment and have included ‘non-compete clause’ in the 2023 Sales Agreement with each other. But while the clause will guard against deliberate actions to undermine one another, it cannot completely exclude competition given the multiplicity of divergent interests arising from the different agreements between themselves and third parties. Importantly, while this is helpful, it is only one aspect of the challenges ODC faces. An even greater one is the lack of strategic blueprint based on its mandate that can serve as a single frame of reference for current and future decisions especially during poor performing markets.

Minerals Development Company Botswana (MDCB)

Institutionally, Botswana’s environment for managing investments in minerals continues to evolve. In 2012 the Government added another company to its portfolio, albeit not confined to the diamond industry. The Minerals Development Company Botswana (MDCB) was incorporated as a private company. Its mandate is ‘to invest in and out of Botswana’ – (https://perspectives-cblacp.eu/minerals-development-company-botswana). The intention is to achieve this by acquiring equity and managing mining and minerals assets on behalf the Government. MDCB is intended to optimize, diversify the Government’s mining portfolio, and provide Botswana with commercial and technical advisory services. The board of the company is appointed by the Cabinet upon recommendation from the Minister of MMGE.

However, implementation of key aspects of its mandate has been slow. As seen from the exclusion of the company from government negotiations leading to the acquisition of shares in HB as well as negotiations with De Beers. In both cases, responsibility for strategy and investment decisions rested with other arms of government and not MDCB as is provided in the company’s mandate. The MDCB leadership team was not invited to participate in the negotiations for the renewal of the Debswana Sales Agreement with De Beers until May 2023 which was more than two years into the process and only two months to the conclusion of a principle agreement. Equally, it was only after 2 years following incorporation in 2017, that Government’s 15% equity in De Beers Group was transferred onto the books of MDCB and a representative of the company on the board of De Beers Group only in 2023. As of October 2023, equity in Debswana and DTC Botswana had not been transferred and was still held directly by the Government.

The question of the company’s role on the boards of entities in which the Government is invested is an important one because it has direct bearing on MDCB’s ability to execute its mandate. Non-Executive appointments to the boards ensure access to information on company operations, risk oversight, protection of shareholder interests and identification of future investment opportunities. So, though not explicitly stated in the company’s mandate, from a governance point of view, it’s near impossible to fully empower the board and executives of MDCB without such privileges. Yet as of October 2023 seats on a number of boards of the diamond companies continued to be assigned to civil servants and not the executives of the holding company as one might expect. The question is, were these decisions an oversight or a conscious one? Either way, the status quo deprives the shareholder of the single point of reference that an investment holding company typically provides on matters of strategy, governance, and portfolio performance. From the few observations above, and from an institutional viewpoint, the operations of the SOEs offer an inconsistent trend. Using a governance lens, some decisions, arrangements, processes, and outcomes work well but others do not and may require consideration as illustrated below. But first, a word on the importance of governance as a tool for evaluating the management of SOEs.

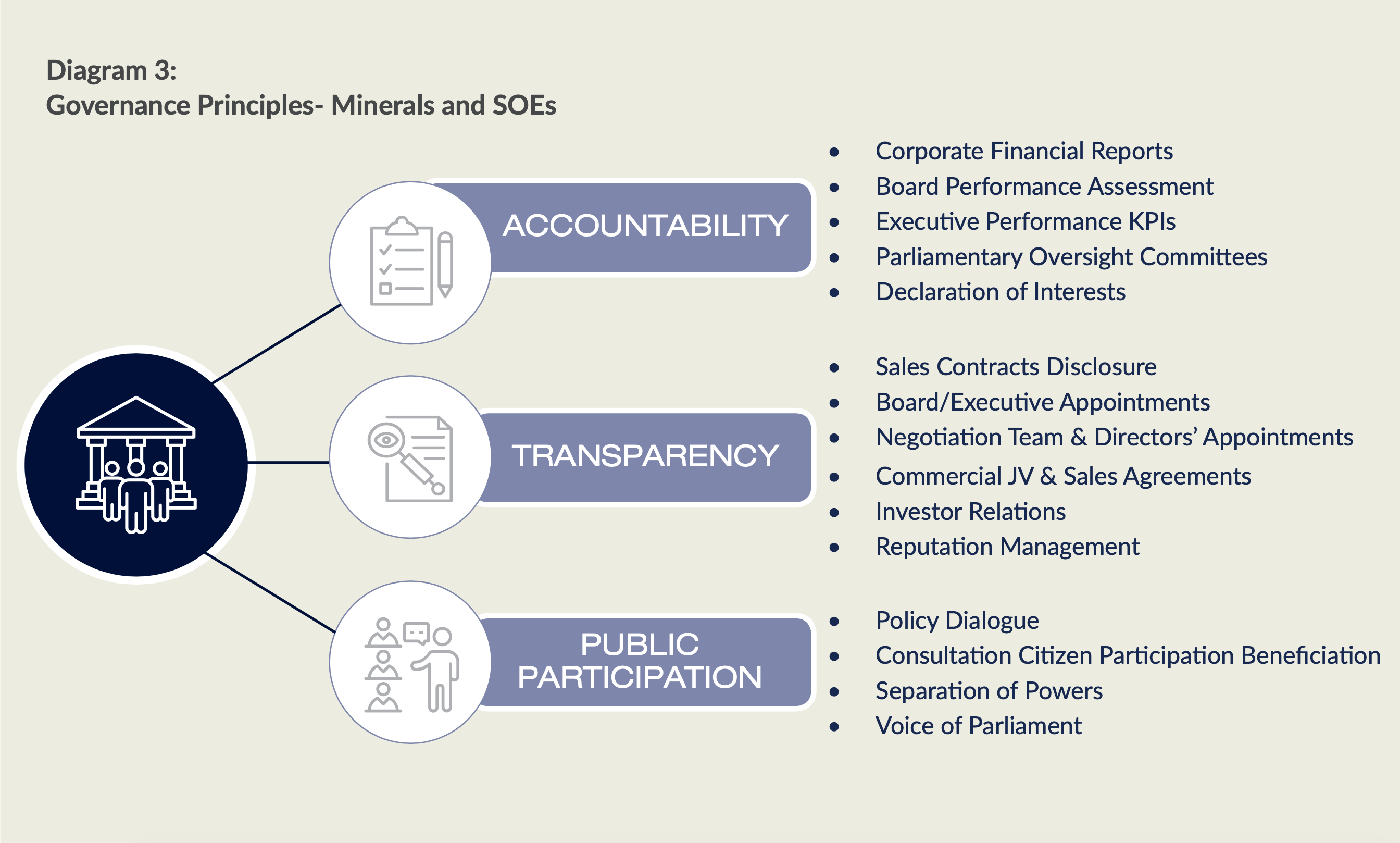

According to the US based Natural Resources Governance Institute (NGRI), adherence to governance principles is critical for successful management of SOEs in natural resources including minerals. – (Anticorruption Guidance for Partners of State-Owned Enterprises | Natural Resource Governance Institute).

What Has Worked

Negotiation Outcomes

The increase of Botswana’s share of Debswana production allocated through ODC is a good outcome on many fronts. It enables the Government to have a greater say over the marketing of the country’s most prized asset. It increases leverage in relation to De Beers. In the face of limited rough diamond supply globally, it places the Government in a position of advantage relative to buyers. The supply provides the necessary critical mass to pursue the goal of making Botswana a centre for rough diamond trading and as such is potentially transformational. For instance, from this position of advantage arises the opportunity to reduce reliance on De Beers including technologically because by partnering with national and international institutions of higher learning in R&D in mining, sorting, and valuing, Botswana can build capacity. But the presupposition is that the necessary policies and strategies are put in place to leverage the position while enhancing the value De Beers delivers instead of pursuing a one or the other philosophy. This implies that the incremental percentage share from 30, to 40 and 50% will be accompanied by a systematic plan to progressively build capacity and minimize market risk.

Institutional Arrangements

The creation of the two SOEs, their respective mandates and strategic goals are timely and have the potential to contribute towards Botswana’s ambition. Their respective governance structures are clear and consistent with corporate governance norms and therefore lay the foundation for potentially maximizing the value of Botswana diamonds. ODC is the vehicle through which Botswana can be a centre for rough diamond trading, promote greater value addition and increase returns on investments made in companies in the diamond value chain. With the right partners ODC can also be the champion for the Botswana diamonds brand both in the rough and retail market.

In a country in which the Government is entitled to equity in all mineral projects, a special purpose vehicle to hold the investments, minimize risk and maximize rewards is vital. The creation of MDCB ensures that a dedicated team has oversight of investments by the government and that it has a voice on boards of companies in which Botswana has a stake. It separates investments from the regulatory arm, from mining, sorting, valuing, and marketing entities. From a governance viewpoint, this is desirable because it ensures separation of duties, clarifies lines of accountability, and builds specialist skills to protect public interest.

But just as regulatory oversight calls for specialist technical skills, knowledge, and an appropriate institutional culture and autonomy, so too do commercial entities. This therefore means that unless the two SOEs, the board and management benefit from such an enabling environment, the above potential is unlikely to be realized. Of specific importance are two factors. The first is the need to avail the correct skills that are consummate with the level of investment and associated risk. That is to say, the investment holding company requires portfolio management expertise and industry specific commercial know-how. The second is creating the space in which those delegated to run the SOEs have the freedom to manage the two companies as commercial entities and not mere extensions of the power base of public institutions. Anything short of this risks underperformance.

Price Discovery

The Government previously relied exclusively on De Beers for information on the market and prices for rough diamonds. As a shareholder this means unvetted access and the ability to make demands on the boards and management for De Beers Group consistent with shareholder rights and privileges. But to the extent that one of ODC’s objectives was independent price discovery, this goal is being met, and ODC can offer additional pricing intelligence to the Government based on the results of the company’s own auctions. In the process the company will successfully transfer skills and knowledge of rough diamond marketing which are essential for future negotiations. The caveat is that the Government is clear over the specific nature of the additional information and market intelligence beyond that which is available through De Beers and the unique use to which the information is being put. The additional knowledge should augment capacity to negotiate with De Beers and other partners and bodes well for institutional strengthening. Otherwise, the decision is an exercise in duplication of resources between two of the Governments own companies.

Revenue Generation

At US$1b of annual sales for the last two years, ODC will be a significant contributor towards national coffers. According to a Bank of Botswana report this represents nearly 50% of that year’s diamond revenue. That said, information on the company’s operating costs, free cash flow and revenue paid to the Government as a shareholder is not publicly available. In the absence of the data and a comparison to De Beers’ sales performance, the financial picture is incomplete. Importantly, on matters of the public’s right to information the lack of financial disclosure goes against transparency and accountability norms.

Branding Botswana Diamonds

Given that ODC only sells Debswana goods, this offers the Government an opportunity to brand Botswana cut and polished stones. This opportunity was enhanced in June 2023, through the Pula Diamonds for Development Fund and the decision to collaborate with De Beers on the matter. Rappaport’s announcement that it would classify Botswana diamond ‘Green’ on its price book is an added bonus. Given Botswana’s partnership with De Beers a branding strategy is within reach. Though proprietary and therefore subject to negotiation, one way of leapfrogging the process is deployment of De Beers’ Forevermark laser imprint technology that has been successfully tried and tested and is now a global retail brand. De Beers and ODC offer a window of opportunity for the parties to leverage each other’s strength rather than compete with one another. It also opens the way for Botswana’s potential entry into the diamond jewellery market. All the factors above offer Botswana diamonds an additional advantage for the stones to potentially fetch a premium. The agreement for ODC to contribute to advertising presumably is partly in recognition of this. But positioning a consumer brand and advertising a luxury commodity is a long-term and very costly endeavour which is nevertheless unavoidable given Botswana’s goals.

Testing De Beers Marketing Model

This matter is another one that presents a delicate balance of risk and rewards. Firstly, ODC’s marketing experience offers the Government valuable data and information to assess the value or lack thereof of De Beers marketing model. However, the question is whether the data has been used to make the latest determination with respect to the production sharing arrangements of June 2023, negotiations with Lucara Diamonds, HB and De Beers. If it was not, the Government has missed an opportunity to deploy fact-based information to revisit its negotiation strategies, (and perhaps policies) and thereby strengthen its position.

Citizen Empowerment

This move is a double-edged sword in that on one level it is a welcome initiative to facilitate citizen entrepreneurship especially in mineral resources investments. But it also a first step towards the creation of a potential elite class wherein traditionally minerals benefited all citizens equally with the Government as the paternal figure. In the past citizen empowerment initiatives in agriculture, commerce, and industry were introduced in the hope the outcome would be economic diversification. None have had a meaningful impact so far. The fact that citizens can buy an export rough rather than being required to process particularly begs the question of the additional value the sales bring to the economy. Either way, based on sheer public sentiment it is hard to argue that citizens should be excluded from the diamond industry in perpetuity. To be clear, social or political capital is no substitute to well thought out and consistently implemented mineral development policies.

What Can Be Improved

Performance Relative to De Beers

One of the main goals for setting up ODC was to test the auction model against De Beers sales contract. So, without the Government evaluating performance to reliably determine that increasing the value of diamonds sold through ODC generates greater financial and economic value for the citizens of Botswana, the justification lacks policy context, and objectivity. Equally, without a detailed risk analysis and a strategy for mitigating market risk in the face of greater financial exposure on the part of the SOE, the company risks exposing the country to adverse impacts of market volatility. So, though lauded in political, media, and civil society circles in and outside of Botswana, on matters of governance, institutional discipline, and due process, public sentiment is no substitute for fact-based economic development policy rationale.

Supply to Botswana Factories

ODC was not obliged to supply Botswana cutting and polishing factories and up to October 2023, HB was treated differently from the other companies in Botswana. The decision was not based on policy but on outcomes of bilateral negotiation with the investor based on the investor’s strategy and not a stated policy amendment. Nevertheless, a decision to offer sales contracts to Botswana factories has since being made post June 2023. This fractures the policy landscape. For instance based on the March 2023 announcement, the scope and essential conditions of the HB contract are vastly different from the rest. That is to say acquisition of state equity and the sale of special Debswana stones. This is problematic from a governance perspective because it distorts institutional arrangements on negotiating and supplying Botswana-based cutting and polishing factories.

A noteworthy matter is the continued focus on export of rough diamonds by successive administrations. This is contrary to the country’s Mineral Policy and strategy to leverage Botswana diamonds to grow the cutting and polishing industry. Based on three important reasons, this is inexplicable. The first is the progressive increase of ODC’s share of supply by Debswana from 25% to 50% and the fact that it does not focus on embedding this policy. The second is that the Government’s decision does not build on progress made in leveraging supply to attract investment in cutting and polishing. Instead, the latest decision charts a parallel path and potentially undermines gains to date. Lastly, its sets a dangerous precedence for future administrations and for opportunistic foreign investors to set the tone instead of taking the lead from Botswana’s policymakers.

DMCC Arrangement

The MoU between Botswana and Dubai is another demonstration of policy inconsistency and parallel value addition policy pathways that lack coherence. One can see how increasing ODC supply will increase volumes of Botswana diamonds exported to the UAE and enhance Dubai’s goal to be the world’s largest rough diamond global diamond centre. What is not clear is how this advances Botswana’s own goals. On the contrary, while the move adds to Dubai’s attractiveness as the place to conduct business, it detracts from prospects for Botswana to be that centre. The irony being, the 2006 Sales Agreement between Botswana and De Beers which gave birth to Botswana’s cutting and polishing industry and later the relocation of De Beers rough diamond distribution operations to Botswana, was among others intended to enable Botswana to work towards leveraging Debswana and DTC Botswana to create such an opportunity. But little has been done to create the necessary commercial ecosystem that Dubai offers the world. So, rather than Botswana capitalizing on its diamonds, Botswana will instead potentially undermine the country’s ability to maximize the value of its diamond wealth. This is counter-intuitive and illustrative of policy incoherence.

Complex Marketing Structures

The structure depicted under Diagram 2 above does not augur well for institutional role clarity, capacity building, risk mitigation and accountability. The complexity can potentially impede oversight and mask inefficiencies, leading to value destruction. In addition, the cost of operating the companies will potentially reduce the Government’s return on investment and revenue. Yet, there is no record of an assessment of the potentially adverse effects and specifically a potential drop in revenue from De Beers Group following the reduction of sales from Debswana to the company. This exposes the Government to potential risk of a reduction or an inconsistency in the timing of receipt of public revenue.

Due Process

Relations with Investors

Investment in HB Antwerp

Corporate Governance

The corporate governance structures of the SOE are above reproach. However, executionally there is room for improvement of governance standards especially on matters of policy coherence, public voice, and regard for due process.

Even though as private companies ODC and MDCB legally have no obligation to report, engage and/or consult directly with the public, given citizen ownership of diamond wealth and intergenerational impacts of their operations, it is hard to argue that the companies should neither be subject to higher governance standards nor greater public scrutiny. Therefore, confining their oversight to the letter of the law falls short of transparency and accountability principles.

The Executive Branch of government is fully empowered to use discretionary powers in running affairs of State and this is neither in question nor should it be. That said, on long-term economic development policy and institutional matters, unless the exercise of such powers gives regard to potential negative impacts, and the need to strengthen public institutions, such actions could be self-defeating.

Conclusion

Like De Beers, ODC has done well by leveraging rough diamond scarcity and high margins to generate public revenue by selling Botswana diamonds much of which are exported by clients. Yet, on thinking about it, the unique value proposition for establishing ODC lies in the fact that as a company owned by the State, it has a higher cause. That it will surpass economic deliverables gained from Botswana and De Beers’ arrangements. Among others, this means using its access to State resources and the powers of all arms of government to go beyond merely generating public revenue by embedding national development policies into its fabric to deliver intergenerational value beyond the life of the deposits. Indeed, based on Botswana’s free market economy principles in which the State leaves enterprise to private entities, these principles are the justification for setting aside this ideology. The assumption is that, unlike a private company, the SOE is not merely driven by the interests of shareholders, but by the needs of a whole nation. Yet ODC’s strategies do not speak to these fundamentals. Instead, ODC’s operating model is a modest variation of arrangements with De Beers. The model smacks of the political economy with no meaningful difference from the halfcentury-old export-orientated Debswana business. This begs the question of, as a company conceived and established purposely to do better, should ODC not be held to higher economic and moral standards?

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.